Illustration by Philippe Meyrier

Condors over Cuzco

by Ana Beker

Illustration by Philippe Meyrier |

Condors over Cuzco by Ana Beker

|

Ana Beker, the daughter of Lithuianian immigrants, had been a keen horsewoman almost from the day of her birth in Argentina. “One day,” Ana writes in her book, “Courage to Ride”, from which this extract is taken, “I went to hear a lecture by the Swiss-born Aimé Felix Tschiffely, who had been a schoolmaster in the Argentine town of Quilmes, and had performed the feat of riding from Buenos Aires to New York with his two horses Mancha (‘Spot’) and Gato (Cat’) who all became world-famous after their achievement of the journey. He gave a full account, accompanied by pictures, of his progress over 10,000 miles of marshes, rivers, mountains, fenland, forest and desert in the New World.

After the lecture I obtained an interview with ‘Chifeli’, as he was

generally called. I told him I was

planning to ride Ottawa, Canada, a 17,000 mile journey that would surpass his

own. Tschiffely stared at me for a

moment in amazement. Then his

characteristic, indulgent smile appeared. He

expressed the view that it would be impossible for me to succeed in my plan

because I was a woman!”

Undeterred, the young Long Rider headed towards Canada.

Sadly, Principe and Churrito, the two horses she set out with, died in Bolivia

– coincidentally within a few days of each other. This selection from her book, “Courage to Ride”, begins

soon after Ana was given two new horses which enabled her to continue her

journey.

| Famed Long Rider, Ana Beker, is seen riding into

Victoria, Mexico in the early 1950s - on a trip which created a sensation

from Argentina to Canada.

Click on picture to enlarge |

We soon reached the further bank of Lake Titicaca and I

then had to choose between proceeding along easy roads which would lead me a

long way round, or following the tortuous Indian tracks across the mountains.

I decided to take the latter course.

But those Indian tracks scarcely deserved the name and were barely

suitable for human beings, much less for the weight of horses.

And they continually staggered and often fell to their knees as if they

had lost heart altogether. Some ten

miles from Titicaca the mare missed her footing on a very steep slope and went

reeling and sliding downhill, with me on her back, till a few good-sized rocks

brought us to a standstill. I was

bruised all over and feared that the mare might have done herself a serious

injury. Meanwhile Luchador had

taken fright and got into a position which might well have ended in a similarly

dangerous tumble. The mare, whose

name was Pobre India, got to her feet luckily without much trouble and I then

had to face the task of calming the two animals while trying to keep my balance

on the slope; this operation took

over an hour. At last I succeeded

in mounting Pobre India. I could

not change to Luchador because the mare was a bad follower, and no good as a

pack-horse.

After this troublesome passage, I entered Copacabana,

where the inhabitants gave me a kind reception. The chief of the frontier police, Captain Ciro Montaño, wrote in my travel diary: ‘I wish the valiant Argentine horsewoman, Ana Beker, every

sort of good fortune in her unparalleled feat of endurance and earnestly hope

she may acquire for her country, and all devotees of sport in this continent the

laurels gained by her athletic prowess, the first of its kind ever to be

recorded. Good luck and may God be

with her.’

At the Kasani frontier post, where Bolivian territory

ends, I saw, for the last time during my journey, the red, yellow and green flag

of Bolivia. It was the 14th March,

1951. Then I set foot in Peru.

Customs formalities hardly existed, for both Peruvians and Bolivians

consider an Argentine citizen to be practically a compatriot.

I was to leave Bolivia with some sad memories, for in

that country where the landscapes had made so deep an impression on me, I had

left my two dear companions; Principe

and Churrito lay buried in the Bolivian earth.

I went my way without them, but I should never forget them nor the hard

yet not unrewarding roads we had travelled together.

In the first Peruvian town I came to the authorities

decorated my diary with ribbons of the national colours, red and white.

My first contacts with the aboriginal natives of that

beautiful country, where I was later to find so much to admire, proved far from

agreeable. It just happened that to

begin with I came across nothing but the most poverty-stricken little hamlets,

where I was even obliged to witness a scene in which certain of the inhabitants

picked lice off the bodies of others and subsequently ate the insects.

They spent their primitive existence in huts of wood and straw.

But they possessed a rude kind of organisation, for in every village and

district a headman ruled, to whom every traveller of an unusual sort, like

myself, who might arrive at any hour of the day or night, had to report.

On one occasion I let my horses graze at the side

of the road an Indian woman immediately rushed up to them, making signs

to me that the animals could not be allowed to eat there.

She told me the same thing in Kechuan, the Peruvian Indian dialect, and

repeated it in bad Spanish. As may

be imagined I ignored her protests. She

then, in a fearful rage, uttering exclamations which I suppose were insulting,

engaged in a rather comic performance. With

all the haste she could muster she began tearing the grass out of the mouths of

the horses. But the animals, hungry

as they always were on such occasions, ate so fast that her interference did not

succeed in depriving them of their meal. I

could not help laughing as I watched her. The woman’s fury rose to a climax. She seized a stick and started beating the animals.

Luchador, the grey, let fly twice with his heels and only just missed the

obstinate creature’s head. Thereupon,

evidently supposing that I would be an easier mark, she advanced upon me,

flourishing her cudgel. I picked up

and raised my whip. As it was

necessary to give her a fright and send her packing I told her that she would

regret it if she dared to attack me. She

instantly bent down to snatch up a stone and the next moment it went whistling

past my eyes. She followed it up

with a further charge, waving her stick.

I shouted at her in my best patois:

“If you want to fight, come on. You

can taste my whip and a bullet from my revolver, too, if you like!”

The woman’s attitude changed in a flash.

She spun round and tore off as fast as her legs would carry her till she

was out of sight.

I had been quietly watching the grazing horses for some

time when I heard some deafening yells; some

fifty people, men, women and children, were running up the road towards me,

screaming at the tops of their voices. Next moment a shower of stones rained down on the animals and

myself. One of these missiles

caught me such a hard blow on the knee that I could not bend it for quite a

while. Two pretty big stones hit

the mare’s head and brought her to her knees, though she stood up again

directly afterwards. There was

obviously no time to lose; I drew

my revolver, sprang onto Luchador and galloped bareback full tilt at the

Indians, firing two shots in the air as I did so.

This had the effect I had anticipated.

The whole crowd scattered, each one running as if the devil were after

him.

This incident did not make me bear the Indians any

grudge, for later on, as I shall relate, I received many benefits from them.

I was always delighted when I met, as I rode along, one of those little

Indian boys, with his round, shining face, resembling a copper coin, his

circular hat and his ragged little cloak, leading by a halter a paco, one

of those superbly graceful animals belonging to the llama family and so typical

of Peru. When their wool is fully grown it covers them all over, falls

over their eyes and nearly sweeps the ground, as if they were dressed in a large

blanket. They are a different breed

from the alpaca and vicuña of Peru.

My arrival in Cuzco, or rather my short stay in that

city, was unforgettable. I shall

always remember this city of the Incas, with the gigantic snowy peaks of

Salkantay and Ausangati dominating the most impressive of all horizons.

I took the opportunity to admire, among other

archaeological treasures, the imposing ruins of the buildings of the Inca

period. One has always heard a

great deal about them, but it is only when one sees them with one’s own eyes

that one is overcome by the magnitude of their achievement. As I drew near the remains of the Inca city of Machupichu I

saw that it lay penned between the peaks of the Andes in the wildest possible

surroundings, near the clouds caught in the snare of the mountain tops, as

though we had left all other earthly things far below us.

The name of the city means ‘Ancient Summit’ and few

places in America or in the whole world can compare with it for the grandeur of

its situation in the Urubamba gorge. It

is astonishing to think that buildings could have been constructed at so

tremendous a height. Obviously the

native workmen had to begin by cutting vast stairways of thousands of steps in

the living rock, as well as the whole system of stairs, terraces and platforms

which apparently served as means of communication between the temples, houses,

palaces and tombs. The monument

called the Torreón, or great tower, standing

on a huge soaring rock of formidable dimensions, impressed me more deeply than

anything else among the ruins.

I also visited the ruins on the banks of the Vilcanota,

at Pisac and Tampumachay; the

latter are said to be the remains of the residence where the Inca himself spent

his leisure.

The whole neighbourhood might be called the Kingdom of

the Rocks. It is the living rock

which gives it so impressive a character of eternal permanence.

The towers, the observatories and the mighty buttresses of every

stronghold are built of rock, unbroken slabs nearly forty feet high.

There are serried ranks of rocks, rocks set on end and gigantic hewn

rocks such as are found in the ruins of Ollantaytambo and all the walls built in

the Inca period, vast assemblages of geometrically shaped and polished stones

that bear mute witness to the immense labour that must have been required and

the impregnability of the result.

I gazed for long at the twelve-cornered stone in the

street called Hatunrumioc at Cuzco, which is supposed to be one of the oldest

and strangest monuments of ancient Peru; it

is certainly a comprehensive example of the mysterious art of the Inca people,

being embedded in a still existent house, once the Hatunrumioc Palace.

I also explored the amphitheatre, with its walls resembling a series of

thrones, among the ruins of Kenko.

Precious specimens of colonial architecture can also be

found in Cuzco; not for nothing is

the city called the archaeological capital of South America.

I am no archaeologist, nor am I writing a book on ancient architecture,

but it was long before the vision faded from my memory of such colonial

masterpieces as the cathedral and the Convent of Mercy.

Stirred to wonder and admiration as I was by such

impressions, it was the Andean landscape itself, nature’s own wild, free and

inimitable architecture, that most captivated my mind.

Some soaring crag, leaping to the very sky from its escorting squadrons

of rocks of a thousand varied shapes, took a deeper hold upon my imagination

than any of the works of man.

After leaving Cuzco I was riding through open country

when I caught sight of a large body of horsemen. As they drew nearer I noticed that many of them were well

mounted and rode in expert fashion, with no resemblance at all to the Indian

style. There were, indeed, some

aboriginals among them. But they

looked quite different from those with whom I was familiar.

At first I felt rather uneasy, thinking they might have

some intention of attacking or robbing me. But when they came within earshot I could hear them cheering

me enthusiastically. They welcomed

me with the greatest kindness.

They all escorted me to a big country house in the

neighbourhood, the property of Señor Abel Pacheco. It was this courteous and amiable gentleman who, after he had

taken leave of me himself in the city, had sent out his servants and friends to

bring me to his estate. On arrival

there I was entertained, with a hospitality I shall never forget, by Señora

Elen Gonzalez, a friend of the owner. The

time I spent on this estate was one of the most enjoyable stages of my journey.

It was a long time since I had seen country-bred horsemen with real skill

in riding, though here they did not achieve quite the same high standard of

devotion, versatility and mastery of equitation as the gauchos of my own native

land.

The contrast with Argentina became still more marked

when, shortly afterwards, I found myself in the most precipitous region of the

Andes, where there were no roads and the peaks and gorges of the landscape

presented a continuous panorama of terrifying grandeur.

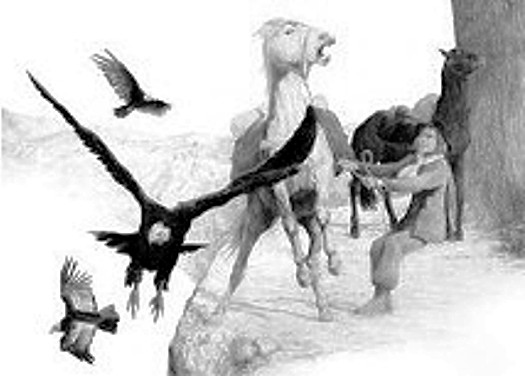

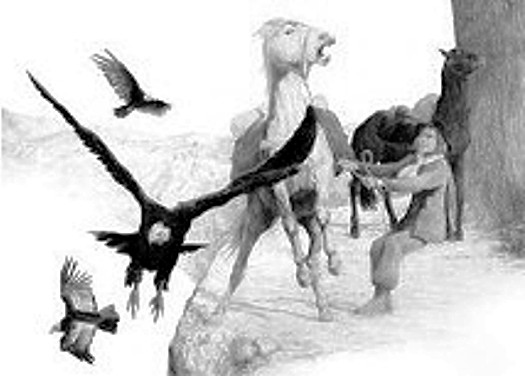

It was soon after this that I was confronted by an

impressive and alarming spectacle that will never fade from my memory.

It happened while I was sitting on the edge of an extremely narrow and

winding path beside a precipice and was deep in contemplation of the mighty

buttresses and tremendous cliffs of the mountains, in all their awe-inspiring

splendour. The horses stood a few

yards away, also taking great care with their movements, for in this sort of

country one must never forget that one false step might send one hurtling into

the abyss. Luchador had gone

slightly further off in search of jujube-trees, which grew at rare intervals

among the rocks.

I had already watched on several occasions the majestic

flight of the condors, as they passed between the crags or alighted on them.

When one of these birds perched on some towering crest and stood outlined

against the dazzling sky in an attitude of intent vigilance, one felt as though

in the presence of a true king of the Andes.

Suddenly I saw a condor of great size sweep by, flying

very fast, like a diving aircraft. It

almost touched Luchador. The first

condor was followed by another. Then

came three or four more. They flew

round in a wide arc and then returned to pass the horse again.

The animal showed distinct signs of uneasiness.

One of the great birds, as it shot past, dealt the horse a violent blow

with its wing. The next followed

suit. Then, to my own terror and

amid the panic-stricken plunging of Luchador, the huge birds started striking at

the animal right and left, with their enormous wings. After a moment I realised what they meant to do.

They were trying to make the horse lose its footing on the path and roll

down the precipice into the chasm below.

I reached Luchador just in time to seize his bridle and

prevent his blindly stumbling movements from sending him over the edge.

When the condors saw me come to the rescue they rose

slightly higher in the air than they had before, but only to return to the

charge. They seemed furiously

determined to achieve their purpose. A

regular struggle ensued, for the horse became unmanageable at times in his

terror. I kept yelling at the big

birds and waving my arms like a windmill to frighten them away.

At last they flew off to a short distance. I then tethered the horse to a heavy rock and went back to

where I had left my baggage. I

fired three or four shots from my revolver.

The reports sent the great birds far enough away for me to lead the

horses to a less exposed and precarious spot.

This episode was one of the most terrifying of my whole

ride. The ferocious birds stayed in

the neighbourhood for some time before they finally vanished, disappointed of

their prey.

I had not realized that condors would attack large animals in such a way but I heard later that they often do adopt these tactics in the case of donkeys, mules or horses of no great size which have been left to themselves due to sickness or old age. The birds are easily able to make them lose their footing in steep places and fall over the precipices by attacking them in the manner described. When the animals have been killed by the fall, condors arrive from all directions to feed on the carcases till they have picked the bones clean. I myself saw on a steep slope, near Abancay, a lean old mule in poor condition, which had no doubt strayed from a drove on the march, attacked by condors in this way. They knocked the animal down, and as it rolled downhill struck it with their wings. I entered the ravine into which the animal had fallen and saw the condors furiously tearing and pecking at it. Dozens of vultures suddenly appeared from heaven knows where, for I never saw them come, and circled in the air above the carrion. When the condors had satisfied their hunger the vultures replaced them; between them they left very little of the hapless mule.

"The

Courage to Ride" by Ana Beker is available from

Barnes & Noble.

|

Click here

to see the world's largest collection |