Call of the Wild

by

Megan Son

|

|

Call of the Wild by

Megan Son

|

Alaska is synonymous with adventure. From the shimmering lights of the aurora borealis to the expansive glaciers, the region is well known for its extremes of terrain and climate. Megan Son tells how she crossed this ancient and rugged land on horseback

“We would be like the pioneers – we would discover along the way.”

Our aim was to cross Alaska with horses, south to north, covering over 1,300 miles in four months. Never mind the fact we had never undertaken such an expedition before: we told ourselves we would be like the pioneers – we would discover along the way.

Our expedition consisted of five travellers; myself, an American writer; two French photographers and writers, Laurent Granier and Philippe Lansac; and two horses, purchased in Alaska especially for the trip. They were the bomb-proof 11-year-old Appaloosa gelding Boogie, and Chevelle, a five-year-old skewbald, known as a ’Paint horse’ in the US.

The pioneers knew little about Alaska when they first arrived in Valdez in 1898, looking for an overland route to the Klondike gold fields of Canada. As we headed out of this picturesque port town in the southern region of the state, we were optimistic about our trip. Unfortunately, we were met with rain – we hoped the Alaskan summer would not fail us.

Bypassing the spectacular Keystone Canyon and taking the Goat Trail, one of the original routes into the Southeast’s interior, we soon came face to face with a fresh challenge, as Chevelle slipped on a bridge just three days into the trail, and almost tumbled off it. Our nerves raw, we headed past Worthington Glacier into the thick spruce forests along the riverbed, then continued on towards Chitina, previously a railway hub linking Kennecott with the sea, with views of the mighty Wrangell Mountains in front of us – Bear country. In spite of the gun perched on Philippe’s shoulder that was supposed to bring us a sense of security, we knew nothing could be taken for granted in such an unpredictable land.

As we dropped down into the vast Copper River valley, fish wheels (salmon traps) dotted the banks, from which local fishermen scooped out salmon for subsistence. The towns of McCarthy and Kennicott were next, the latter being home to the 14-storey wooden mill building from the town’s copper producing days, nestled in the mountains of the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park.

We were delighted to encounter with the 17-strong Pilgrim family, who kept chickens, goats and dogs, and hunted and fished to survive. They all had unique skills to contribute to the livelihood of the family, and even make their own entertainment – every member of the family played a musical instrument. Experiencing these cultures with Boogie and Chevelle enriched our experience and we marvelled at the family’s seemingly fulfilled existence, living off the land alongside their treasured animals.

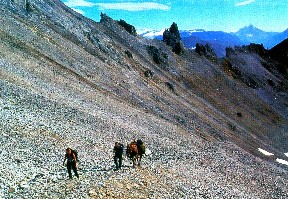

| Despite the rugged terrain,

the horses climbed easily, even though their feet were sometimes full of

ice. Photograph by Laurent Granier

and Philippe Lansac |

Climbing up the Kennicott Glacier, we rode on to the famous Bonanza Mine, where prospectors Clarence Warner and Tarantula Jack Smith first discovered copper in 1900. Next, we rode across the tundra that spread out either side of the 1,000m-high Denali Highway. By now, the cooler temperatures of autumn were embracing us. Trails abounded, and we found ourselves knee-deep in mud, losing saddles and equipment along the rocky, wet paths. Insects attacked us relentlessly, but we were greeted with rainbows and glaciers as we rode parallel to the majestic Alaska Range. The horses had amazing spirit, and we are awed by the trust they put in their somewhat inexperienced leaders.

As we left the burning colours of autumn behind us and faced the mighty expanse of the Yukon and the Arctic Circle, we knew winter was upon us. The jagged peaks of the Brooks Range loomed.

Atigun Pass was steeper than it looked, and was covered in snow. But there was little time to complain, and we started the ascent, rain turning into snow and pelting our faces. The horses’ hooves were packed with ice, yet amazingly, they climbed fairly effortlessly. Then the euphoria of crossing the pass dissipated, leaving us shivering and miserable.

We were lucky to have decent gear that kept us mostly dry, but awoke to frozen shoes and stiff shoelaces. Squeezing our feet into them, willing them to thaw, we noticed that Boogie was acting strangely. After a warning from a local worker about bears being spotted ahead, we wondered if Boogie was on to something. Since the beginning of the trip I had become somewhat obsessed with bears, reading every pamphlet I could get my hands on – even dreaming about them. Now might be my chance to see one.

As we headed along the Atigun River, we became immersed in our surroundings, the Brooks Range piercing the blue sky – until Laurent called out, “Bears!” I craned my head for a better look – and saw the brown hump of a grizzly. I stopped dead in my tracks, but Laurent and Philippe had already retreated behind Chevelle and me, getting the gun ready. I waved my hands over my head, saying loudly, “We are human. Go away, bear!”

The nearest bear stood up, rocking back and forth to get a better look. We looked at each other – what to do? We turned the horses around and inched back slowly, keeping the grizzly and his companions in sight.

We considered travelling higher up to avoid getting too close to the bears, but then we spotted a pickup truck carrying two rugged hunters. We waved them down and asked whether they would mind buffering us against the bears with their truck, worry and panic creeping into our voices.

“That’s probably a good idea,” the younger one said. “Them horses would make good bear bait.”

Next we headed into the coastal plains; being cold and wet was now part of the daily routine. Even though we were getting closer to our destination, the horses were losing steam. Little did they know that we were almost near the last town on the horizon, ironically named Deadhorse.

Access to the Arctic Ocean is controlled by British Petroleum, which owns several offshore oil drilling platforms and refineries along the North Slope of the Brooks Range and out into Prudhoe Bay. Although we had been declined access many times, we kept asking – we had come too far to give up. Eventually, we were given clearance, and were allowed to reach the Arctic Ocean.

We had travelled over 1,300 miles through mud, rain and snow and endured some challenging times, being supported by local people all the way. And we felt we knew something of the spirit of adventure that had driven those early pioneers to settle in this rugged and beautiful region.

| Note: Megan, Laurent and Philippe have written a book in French about their adventures. Click here to find it on Amazon.fr. |

This article was first published in Great Britain's Horse magazine in November 2004.