A Word from the Founder

|

A Word from the Founder |

|

September 13th 2001

I am not in the habit of explaining my writing. Yet these are strange and dangerous times we are living in. Several people have urged me not to publish the opinion piece which you will find below. I have been told that this is not the time to voice so strong a personal view. Others have cautioned that this website was designed merely to promote equestrian travel and therefore has no place for my personal views on life, horses, and the world in which we live.

As a result, for the first time in my life as a writer I am including, not an apology - for I do not apologize for what I have written, what I believe, or what I stand for - but this explanatory note in which I clearly mark out the difference between the words below, which are solely mine, and the overall mission of The Long Riders' Guild, which is to promote equestrian exploration.

Horses and the World of Islam

by

CuChullaine O'Reilly

I have something to tell

you.

I am a Muslim.

But wait.

There’s more.

I fought in the Afghan

Jihad against the Soviet Union, did my best to take other men’s lives, taught

Afghan resistance fighters how to be journalists, and wallowed in the warm

comforts of self-deluded nationalism that afflicted my Cold War generation.

During the course of my overseas life I took on a new name, Asadullah Khan - The Lion of God, and proudly wore the trappings of 1980s militant Islam. I strapped on a sword, wore many guns, wrapped a fine turban, and believed in my heart that I was doing God’s Will by fighting the Red Menace.

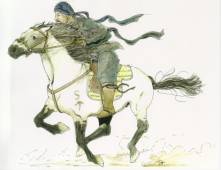

| Life on the North West Frontier Province of Pakistan in the

1980s was frequently short, and often punctuated by violence.

Asadullah Khan, a.k.a. CuChullaine O'Reilly, is seen on his horse Pasha as they made their way across Northern Pakistan.

|

Throughout those

adventurous years I rubbed shoulders with a plethora of killers, conspirators,

rebels, spies and militant Arab fundamentalists including, I now realize,

friends and close associates of Osama bin Laden.

I did all these things in

the misguided belief that I was enlisted in a noble cause, that I was helping to liberate

an enslaved people, that I was serving God.

In fact I was merely an

adventurer cloaking my actions in a disguise of religious righteousness, never

understanding that I, and the many others like me, were being manipulated from

the background by shadowy governments and dubious men.

To make matters worse,

though I publicly adhered to Islam, I was, to be brutally honest, a cultural

Muslim and never a spiritual one. I was intoxicated with the strangeness of it

all, the Oriental mystery, the forbidden, the obscure. So though I bent my knees

in prayer, I never unlocked my heart to the true ideals of the religion I had

ostensibly adopted, namely mercy, kindness, forgiveness, and the belief in the

universal brotherhood of all humanity. I was, by today's definition, a misguided

young religious zealot, fuelled by hate, and convinced of my own spiritual

self-righteousness.

And now, many years

later, my eyes have been opened by a host of personal events, and a series of

good people, to a new point in my life where I quietly practice the religion

which I publicly acclaimed more than twenty years ago in a long-gone and

war-free Ashvagan (the Persian word for Afghanistan, meaning "Land of

Horses"). I no longer wear guns. My sword collects dust and sleeps

with her memories. But most importantly, I try in my daily life to put into

practice what the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) taught, mainly to love my fellow man

and to worship naught but God.

Alas, if my own eyes have

been opened, many still have not.

I see a new generation of

misguided, idealistic, naïve, religiously fervent young men preparing to lay down their

lives in what they deem is a new Jihad, in what they say is a new war against

oppression, in what they do not recognize is instead only the newest

manipulation of their need to believe and belong.

For they, like I once

was, are equally misguided and will be equally misused by another crop of village

mullahs. These priests of discontent are the same type of men I knew in the

1980s, still distorting a great religion, still forgetting the word

“forgiveness”, still too filled with hate to ever practice mercy.

I speak for all young

men, some dead in that war, some doomed to die in this new one, when I say that

though the year on the calendar has moved on since I left Afghanistan, one thing

remains the same. This current lot of believers resemble me and my generation in

that like us they are not able to distinguish at a glance the difference between

political shadow and spiritual substance.

You ask, what does this

have to do with horses and The Long Riders’ Guild?

So I will tell you.

For horses, like

religion, have once again become misused tools of mankind’s collective

unhappiness.

Unreported in the Western

media is the overlooked fact that Osama bin Laden is a keen horseman. The Arab

militant owns several horse farms in Afghanistan. Soon after the New York attack

on September 11th, Osama bin Laden took an oath of allegiance from 500 of his

die-hard supporters. Surrounded by these loyal bodyguards, the Saudi radical

then disappeared into the Afghan countryside, mounted on one of his many fine

steeds.

Meanwhile, further north

in that same unhappy country where I once rode, the Chesterson family were also

swinging into the saddle in an attempt to escape the current war. The four New

Zealanders had been working for an international aid agency in Faizabad, a small

town in northern Afghanistan. Soon after New York was attacked, the Kiwi

refugees heeded local advice and fled across the treacherous Hindu Kush

mountains of Afghanistan. They rode

south on the only road open to them, hoping to reach the relative safety of

Pakistan. Once again, it was horses that changed the course of their lives.

| This rare photograph shows mounted Afghan tribesmen riding into combat against the Soviet Union in January 1980. They are shown leaving Herat, located near the Persian border, a stronghold of equestrian Afghan warriors led by famed Mujahadeen Commander Ishmael Khan. |

Just a few hours ago a report crossed my desk that the famed Afghan mujahadeen leader, Abdul Haq, had been captured and assassinated. I never met Osama bin Laden. I never met the Chesterson family. I met Abdul Haq several times when we both lived as exiles in our adopted home of Peshawar, Pakistan. Abdul was famed for outwitting the Soviets. He was captured fleeing from the Taliban on horseback.

Now he is dead and more are doomed to die.

Thus it would be easy

during this time of global crisis to overlook the enduring truth that binds

humanity and the equine species in a tradition of mutual need stretching back

30,000 years.

Yet in these days of

murder and outrage we need look no further than to Islam, that

oft-misinterpreted religion, to find help in understanding why men and women of

all faiths, of all countries, of all political persuasions still seek comfort in

the presence of these fine animals that so enrich our individual lives.

The Muslim holy book, the

Qu’ran calls the horse, “El-Kheir”, the supreme blessing.

According to Muslim

tradition, Allah created the horse from the wind as he created Adam from clay.

Allah said to the south wind, “I want to make a creature out of you.

Condense.” And the wind

condensed. He then said to the

newly created horse, “I will make you peerless and preferred above all the

other animals and tenderness will always be in your master’s heart. You alone

shall fly without wings, for all the blessings of the world shall be placed

between your eyes and happiness shall hang from your forelock.”

God created horses from

the wind for our benefit and pleasure.

Sadly, we now see horses,

these instruments of God, turned once again into puppets of war.

We have a saying in The

Long Riders’ Guild.

It was invented by Gérard

Barré, that fine

French horseman and equestrian philosopher.

“We should speak no

language except Horse,” he informed me when a handful of us first formed the

Guild.

Those simple words have

collectively guided our efforts as Long Riders from a host of nations reached

out for the first time in recorded history to form an international network of

equestrian travelers residing in every part of the globe.

For in one sense, we Long

Riders have no religion, no nationality, and no home except our saddles.

We wander the world with

our horses in search of superficial adventure, all the while searching for a

deeper spiritual meaning to our lives.

We talk beside our

campfires with other travelers about the hard road ahead, and the mysteries we

have seen on the trail behind.

For unlike those who

restrict themselves to show rings, or other forms of equestrian prestige

transport, we Long Riders know that the higher we ride the further we see.

As I write this there are

more than a dozen Long Riders scattered on obscure trails from Africa to

Argentina. While the majority of people sit panic-stricken in front of their

televisions, these brave equestrian explorers are risking their lives during

these perilous times, determined to continue their global journeys to discover

more about themselves and their horses.

None of these Long Riders

are preoccupied with politics.

Like our ancestors, they

are seeking ancient needs – Grass, Water, Food, Shelter.

A wise man named Yusuf

Ali, once wrote, “Through all my successes and failures I have learned to rely

more and more upon the one true thing in life – the voice that speaks in a

tongue above that of mortal man.”

Wanderer that I am, it took many years for those simple words to sink into my war-hardened heart. There was a time in my earlier life when I only had physical courage. But I now believe that what is more important is the spiritual courage required to dare all in a cause which is dear, so I have laid aside my sword and taken up the pen, hoping to place before you today a faint reflection of my own spirit and beliefs.

| Asadullah Khan, a.k.a. CuChullaine O'Reilly, at the peak of the 13,696 foot high Babusar Pass, located between Azad Kashmir and Yaghistan, the Land of Murder. |

I trust in this time of

global conflict, religious suspicion, political intolerance, and individual

cruelty that we, the Long Riders of the world, will serve as a beacon of what

remains good in the human race, that we will show by our love of our horses and

fellow human beings that we reject the hysteria and signs of war that currently

entrap our brothers, that we will collectively pass beyond any limitation in the

free spirit that defines us individually.

We stand at the threshold

of a new Renaissance of Equestrian Travel, one which will sweep away the cobwebs

of past political problems and let in the full light of international

understanding.

I believe that this will

occur because as our planet grows smaller, a brotherhood of men and women who

belong to the saddle will cement that unity by our belief in a common goal -

the right of free travel anywhere in the world on our horses.

For the first time in

equestrian history it no longer matters where you were born, or how you worship

God. The Long Riders’ Guild represents a safe haven for all adventurous

spirits who yearn to seek the horizon from the back of a horse.

Some day these tragic

events which weigh upon our souls today will be naught but a footnote. Empires

fade. Wrongs will be righted, and the Qu’ran is still right when its says:

“But God, in His

infinite mercy and love,

Who Forgives and guides individuals and nations,

And Turns to good even what seems to us evil,

Never forsakes the struggling soul that turns to Him.”

During these troubled

times mankind’s interdependence with the horse will remain to strengthen those

of us who understand the serenity to be found on the back of this equine

blessing born of the wind.

| According to Muslim belief, in the year 622 the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) journeyed from Arabia to Jerusalem and back in a single night. He was mounted on the Borak, a mythical creature, half human and half equine. This illustration shows the Borak flying over the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, one of Islam's holiest mosques, while behind her is the Tomb of the Prophet, located in faraway Arabia. Among other things, the Borak represents the attainment of an impossible journey, and thus is a fitting symbol for the challenges and rewards of equestrian exploration. |

Thus I conclude with this

thought.

We Muslims believe that

our deeds are personified, that they are witnesses for or against us. Many of my

previous deeds were dark ones born of war and misunderstanding.

Now, after many years,

after many struggles, after many lands, I have ultimately come to believe that I

am only three things.

I am a Sufi, a Scholar,

and a Horseman.

Anything else is but the

dust and mirage of this fleeting image which we call life.

See you on the trail, Saddle Pals.

Asadullah a.k.a. CuChullaine

|

Visit the world's largest collection of Equestrian Travel Books! |

Back to Word from the Founder main page