Forgotten

Heroes

By

CuChullaine

O’Reilly

|

|

Forgotten

Heroes By CuChullaine

O’Reilly

|

In 1912, four riders embarked on a 20,000 mile cross-country trip they hoped would bring them fortune and fame. It was called the ride of the century, a 20,000-mile, 3-year odyssey through desert, mountain, and swamp that four young horsemen dreamed would make them famous.

Instead,

they rode into oblivion.

The

year was 1912, and as George Beck, part-time Washington logger, sometimes

visionary, and full-time horseman explained to his three closest companions,

fame and fortune lay in the saddle, not with the ax.

“Logging

is a lousy business,” he said. “We’re

lucky if we work 6 months a year. In

the meantime, there’s a World’s Fair, the Panama Pacific International

Exposition, comin’ up in San Francisco in 1915.

The gold is there. We have

the nags and gear. Let’s ride to

every state capital in the Union. Let’s

make the longest horse ride on record and get ourselves a reputation.

We’ll win fame. We’ll

write an adventure book. We’ll

put on a show on the midway at the Exposition.

There’s a pot of gold out there and we’ll find it,” Beck assured

his friends.

Beck’s

pals didn’t need much persuading. They

included his younger brother Charles, an out of work railroad employee, Jay

Ransom, a fiddle-footed brother-in-law and Raymond “Fat” Rayne, a skinny

twenty-year-old who was the youngest in the group.

Ransom

and Rayne lived in the nearby village of Shelton, Washington.

The Beck boys called Port Blakely on Bainbridge Island home.

Ransom would be leaving behind a wife.

The other three were ready to follow where the wind blew.

All

four agreed it was a crazy idea from the start.

The glory days of the cowboy were already fading from memory.

Horseless carriages were replacing horse and buggy.

A new industrial era was fast obliterating the lifestyle of free range

riders.

|

|

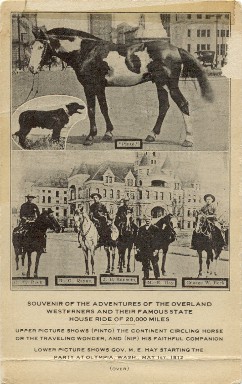

The Overland Westerners (clockwise from top left): Jay Ransom, Charles Beck, Raymond Rayne, Nip, and George Beck |

None of that mattered.

While

Charles, Jay and Fat readied the horses and tack in Shelton, George went to

Seattle, eight nautical miles east on the shores of Elliot Bay, to order

postcards and calendars showing the riders and their mounts, plus their proposed

zig-zag route during the 48 state trip.

Beck

hoped to sell these keepsakes to well-wishers along the way.

In addition, he made a deal with a small Seattle magazine, The

Westerner, regarding the sale of subscriptions by the riders along the way.

The magazine folded soon after their departure and with it went any hope

of even limited corporate support.

But

that fact lay ahead in a future George Beck could only vaguely perceive.

Instead

the morning of May 1, 1912, dawned full of promise.

The original five horses and their riders, now calling themselves the

Overland Westerners, stared self-consciously for a moment into the lens of a

local photographer and then swung into the saddle, headed towards their first

rendezvous with a governor in nearby Olympia, Washington, 18 miles away.

|

|

The

Overland Westerners began their journey at Shelton, Washington, on 1st

May 1912 |

A

few hours later, after having their photograph taken with Governor Hay, they

received a formal “Certificate of Call” verifying their arrival, plus a

letter of introduction to Oregon’s Governor West, a procedure they faithfully

duplicated during the entire trip.

After

the photo session Beck wrote, “The governor wished us luck on our great trip.

After saying goodbye to friends who had gathered there, we were on our

way. We hit up a five mile gait

over the Pacific Highway, which was fairly good for about seven or eight miles,

then the road got rather rough and wet from the recent rain.”

Wet

roads were soon to be the least of their worries as dreams of equestrian

adventure were soon replaced by grueling hardships that became standard fare for

the next three years. While

traveling through Oregon they adopted the last member of their team, an

exuberant Gordon Setter puppy named Nip. After their meeting with the governor in Salem, the

Westerners set a course across the still snow-covered Cascade mountains.

Only

23 days after their sunny departure they discovered their route now barred by

snowdrifts seven feet deep. Following an apology of a trail up the Hackleman Pass, they

passed the night near the summit in a freezing, deserted cabin.

They set out at 4 a.m. the next morning, determined to break free of

this first great obstacle.

“Got

to the snow line at 5 a.m. and then the fun began, although it was better

than we anticipated having frozen some the night before.

It held us up pretty well. But

the horses went through to their belly once in a while.

It tired them out pretty much on the start as it was pretty tough work

and new to them. But when they got

their second wind they done better and got somewhat steadier.

I thought once we would never make her but a fellow can do more than he

thinks he can if he makes up his mind and we made up our minds to go through or

bust,” Beck wrote.

Idaho

treated them more kindly than had the cruel Cascades.

They were invited to step down from their saddles and play in a baseball

game between two rival mining camps. Of

course the playing field was five hours away by buckboard.

Upon arriving all involved were required to chop down enough sagebrush to

lay out a playing field. Thereupon

the game lasted until well after dark, with multiple arguments being settled by

umpire Fat Rayne in favor of the hosts. The

results being a good meal at the cookhouse “that did not cost a cent.”

In

Boise George was invited to ride in the show put on that night by the traveling

101 Wild West Show. He did so on

Pinto, the Morab originally chosen to be the packhorse but fast becoming

George’s favorite mount. Already

the Westerners’ original horses were showing signs of fatigue and saddle

sores. The riders quickly learned

if they were to go on they needed to swap horses with the local populace if and

when the chance arose, a business fraught with monetary peril.

“The

rancher was a nice guy but no dummy and I figured he’d want some scratch,

seein’ as our two animals seemed headed for the glue factory instead of the

rest of the state capitals. The

first deal was open and shut, horse for horse, and we gave the fellow $10 to

boot. The second deal was for a

horse for Charles. The fellow

wanted $25 besides his horse, but I had a rush of brains, and told him he was

getting a real bargain because our horse was famous, ridden by one of the

Overland Westerners. ‘Why he’s

a show piece and you can have barrels of fun showin’ off.’ That got him and we walked away with his nag,” Beck

recalled. “I didn’t mention

sore feet, tender bellies or sore backs, just said he was a show horse maybe

risin’ six or seven years.

In

Montana the folks treated the riders kindly, though Fat’s saddle was stolen

one night in a Helena boarding stable. Well

known local saddle-maker F.J. Nye replaced the saddle and bridle.

But being already penniless, the Westerners were forced to leave their

tent, camera and gun behind as security. All

was not desperate though as they headed towards the Dakotas. George wrote about the cowboy dances where they could sneak a

“short snort from jugs hidden in the haystacks” and fondly remembered

meeting a beautiful schoolteacher he described as “a nice piece of calico.”

The

intrepid riders had no way of knowing that their real troubles were just

beginning. After selling their

winter coats for $1.75 they headed east. Beck

writes movingly of suffering in the saddle as the committed horsemen learned to

fend off hunger with rough bunkhouse humor.

Jay Ransom awoke one night in an abandoned cabin to discover timber rats

gnawing off his hair. Nip had

quickly grown into a valued member of the team, often bringing in a rabbit that

served to feed all five hungry travelers. What

little money they earned from the sale of postcards and calendars always went to

taking care of the horses first. On

the odd occasion when they could afford to sleep in a local fleabag hotel, they

would draw straws to see who would get the single bed, the losers forced once

again to flop on yet another unforgiving floor.

Most nights were spent in hay stacks, barns, livery stables, or

underneath the stars.

As

the months and the miles rolled by the Westerners alternately either froze or

roasted in the saddle. Averaging 22 miles a day, they grew lean and hardened by the

thousands of miles falling behind them on roads that ran the gamut from bad,

muddy, or thick in dust to non-existent. The

little money they spent on themselves went for “a few soft drinks to take the

curse off a few hard drinks.”

At

one town of a dozen houses where they had been invited to stop for dinner, they

turned the horses loose to graze near the railroad tracks. Despite two men

watching while the other two chowed down on meat and gravy, the horses got on

the track and went across a small trestle.

Though the ties were only five inches across, all the horses made it

across except Ladd, Fat’s mount. He

fell through and was penned down with all four legs between the guard rail and

the ties. It took ten men, with two

small boys watching at either end of the trestle for oncoming trains, to free

the terrified horse.

But

their troubles didn’t stop there.

Pinto,

the sturdy fifteen hand Morab and by now the acknowledge favorite of the entire

group, was nearly lost in one of the many treacherous river crossings.

“We

had forded dozens of busy rivers. Jay

tested the stream with a long pole, then rode over to show us how it could be

done. Everything went find until he

got in midstream when Pinto, carrying our pack which slipped, flipped over and

couldn’t flip back. I thought he

was a gone horse, but Jay hung on, flipped him over right side up, headed him

upstream and snaked him to shallow water. I

don’t know how. We all rushed in

and after slashing the diamond hitch got Pinto on his feet.

We lost some grub and a few utensils but we were very glad to escape that

easy by saving Pinto,” Beck wrote.

The hardships drove the men to bond tighter than ever. They rode south with the winter, north again with the sun, eating up the miles and not much else. Summer of 1913 saw them in Washington D.C. where they had gone to meet President Taft. And though poverty dogged their trail they managed to “brush the hayseeds out of our hair and the manure off our jeans” and put on a brave front when meeting various governors and officials.

Ever

the cheerleader and inspiration, George reminded the others that they were

“gentlemen tourists on horseback with a self-appointed mission and not

saddle-hums.” With more than half

of the United States now behind them their rosy future with its pot of gold was

getting close as every step took them towards San Francisco.

With more than 10,000 miles already in the saddle the reception they encountered varied from region to region.

|

The Overland Westerners meet the Governor of New Hampshire |

“You

can’t carry me back to Ol’ Virginny. You

can have my Ol’ Kentucky Home and Carolinny in the Pines.

Phooey! In the South we

weren’t much shakes. Just four

men riding on horseback. The best

thing I can say was it was warm and we all got thawed out,” Fat Rayne wrote.

In

Maine, which they reached in “Ol’ October when it was pert near gone,”

they found “lovely country and fine people, mildly suspicious of four fellows

who had nothing better to do but ride horseback – but friendly

nevertheless.”

1914

came and went, as did state capitals and a host of politicians.

Photographs show the weary men and a string of ever-changing horses

posing in front of numerous grand buildings, their gaunt cheeks and dusty

clothes offering a shocking contrast with the well-fed governors posing beside

them. Only the ever-cheerful Nip and sturdy Pinto seem to be able

to ignore the hard miles.

Another

Thanksgiving on the road found them with more than 15,000 continuous miles

behind them and still too poor to be able to afford a restaurant meal on yet

another lonely holiday spent in the saddle away from home and family.

“Having

no invite for a turkey feed,” Beck recalls, “we moved down the road.

Although we were practically busted, we were thankful for our good health

and for the willing horses which had taken us so far along our trip. To celebrate, we had a hobo stew which we prepared on the

road. It seems a good-sized rooster

got in the way of a rock which Fat happened to throw.”

They

rode into Oklahoma City in November, 1914, and realized they were seven states

shy of reaching their goal. They were singing in their saddles now, through the long,

lonely stretches between isolated ranches and tiny settlements because at last

they were back out West among kindred souls and horsemen.

“These

are horse people, cattle people, out of doors people.

They are on their own and they know damn well we are on our own, and are

not craving sympathy. We can’t

buy a bed or a meal in this part of the country.

It’s all give and no take. They

just want to talk horses and gear and pump us for yarns about our trip.

We don’t have to tell them about our hardships on the trail;

they know all about rough going in a raw new country like this,” Jay

Ransom confided in his diary.

In

early 1915 a Wyoming rancher invited them to go to the corral and “take your

pick if you can ride ‘em.”

George

wrote, “We could ride ‘em. You learn how to ride, no matter which way they twist, after

you have forked a hayburner a few thousand miles.”

At

last only the might deserts of the Southwest lay between them and California.

Bone weary but full of hope they often now rode at night to save riding

the horses through the worst heat of the day.

“We

are on our way again, leaving these good people.

Now we are coming to the part of the trip we have long dreaded – the

desert country. The gila monsters

and tarantulas may seek shade but we must shag on.

There are miles to go before we rest,” Beck wrote.

They

reached Sacramento, their 48th and last state capital on May 24,

1915. They had been in the saddle

for three years and one month, a record 1127 days of that time spent riding.

They had gone through 17 horses on the 20,352 mile trip.

During this time they had spent just $9000 between them.

After their photograph was taken with the governor of California, they

set out for the last stop, the Panama Pacific International Exposition in San

Francisco.

Arriving

there on June 1, 1915, they expected to be greeted by the boisterous crowds,

gathered there to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal, to great them as

homecoming legends.

Instead

an Irish cop yelled at them to “get them hayburners off the street.”

Little

Sheba the belly-dancer was big news. Four

saddle-sore heroes were not. They

came expecting glory. They found

only failure.

Within

days their story and marvelous achievement was rapidly forgotten by an apathetic

public more interested in the outbreak of World War One than four weary men and

their footsore horses.

Beck’s

three companions, tired, broke and broken-hearted, sold their horses and tack

and rode the rails home to Washington. George

stayed on in San Francisco trying to coax a story out of editors and authors.

Jack London, among others, turned him down. With no hope and no pot of gold, George managed to pull off

his last miracle.

He saved his horse.

|

George Peck on Pinto, Atlanta, Georgia, 5th June 1913 |

Pinto

was the only mount used during the journey who had managed to complete the

entire grueling trip. The tough

little 15 hand, 900 pound Morab had long ago left behind his pack saddle and

become George’s equine soul-mate. Beck scraped together enough money to get himself, Nip and

the ever-loyal Pinto passage home on a tramp steamer.

They

arrived back in Puget Sound to no fanfare.

Beck tried to put his recollections into a book but had no success.

“I

wrote it sweet enough but it came up sour,” he said.

That

brief statement could have summarized his life and great adventure.

Beck, the man who had saddled his dream and rode it out, died one night

dead drunk, drowned in a six-inch deep roadside ditch.

Soon after his master’s death, Pinto was sent off to labor one last

time, lugging a packsaddle once again, through the thick, rainy depths of the

Olympic National Forest.

And with them died their incredible story, equestrian heroes, forgotten by generations of American riders and readers.

Back to Stories from the Road Top