A Word from the Founder

|

A Word from the Founder |

|

In Search of Equestrian Freedom

by

CuChullaine O'Reilly

The horse lay dying, although I was too naive to know that.

Overhead the moon was full, throwing down enough light to read a book on veterinarian medicine if I had had one. But this was Kafiristan, a tiny village stuck up in the northern corner of Pakistan where not killing your neighbor was a recent innovation, and besides, I was on my own again as usual.

Of course my trusty friend Ali Mohammad was there. But he knew just enough about horses to throw his leg over the saddle. Sitting beside him on the darkened ground was a nosy, grizzled, old Afghan refugee, a cook at the chaikhana where we had stopped when the horse became critically ill.

"He says to poke a hole in the horse’s stomach to keep him from dying," Ali Mohammad told me, all the while the Afghan kept up his incessant chatter.

I hesitated, not knowing what to do, but certainly not prepared to shove my dagger into the packhorse’s belly on the off chance that an illiterate rustic knew more about equestrian medicine than I did.

So I kept kneeling there, while my other three horses pawed and screamed in fear a few yards away, and I held this dying horse’s head and tried to will him to live.

But of course he didn’t.

He died like the cliché, in my arms, and not quietly either but with a great, painful sigh and a last rattle rushing up from deep down in his throat. The moon beams burned down like a spot light on my guilt. It was 12:17 a.m. and I had let a horse die on my fifth equestrian journey in South West Asia. A cloud of shock descended over my rational American mind. Sven Hedin, the famous Central Asian explorer, had gone on an expedition in the late 19th century and lost nearly three hundred horses. He had considered their passing so insignificant that he mentioned it only in passing at the end of his book.

Yet this was no book. This was no armchair fantasy. This was the brutal reality of equestrian exploration and I was suddenly sick of it. Then my grief was interrupted.

|

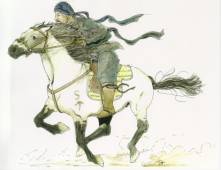

Click on picture to enlarge |

CuChullaine O'Reilly riding along the borders of Yaghestan, the Land of Murder, in northern Pakistan |

"The old man says to cut the horse’s throat quickly if you want to make his meat halal (pure), otherwise the Kafir pagans will eat him blood and all," Ali Mohammad said quietly.

I let the horse’s head down to the ground gently. Already his eyes had glazed over. Odd, I thought, that the departure of the soul takes the light from the body. And then I stood up.

"No. Leave him," I ordered. "It’s bad enough that he died on my watch."

Of course the old man was right again. I had forgotten that this was brutal Pakistan, not home in the United States where animals, especially horses, occupy a special niche in our collective hearts.

The next morning while I was preoccupied the Kafirs skinned and ate my horse, chopped him up into so much cold dead meat, and robbed me forever of many of the romantic notions I had long cherished about the beauties of equestrian travel.

There is only one way to explain why I was out there risking my life and the lives of my horses.

I am a Long Rider, one of a handful of men and women upholding a 6,000 year old tradition of nomadic equestrian travel. But before you ask what the Long Riders are, let me tell you what they are not.

In this age of anonymous air travel Long Riders are not tourists, trail riders or ring riders. They are the equestrian equivalent of saddle borne astronauts, a tiny, hardy band of risk takers and wisdom seekers.

They are unlike tourists, who expend their energy coveting vast mileage yet see nothing more meaningful on their journeys than post cards and casual impressions. Long Riders know better than to become obsessed with finding their destination on a map. They inherit from their horse borne ancestors the knowledge that all maps are flat-faced liars save that sacred document called your heart.

Tourists come back with souvenirs of physical locations but remain inoculated from experiencing inner wisdom. Long Riders travel seeking to unravel the mystery of the oldest form of Equine-Human achievement, that ancient equitation known as Equestrian Travel.

Nor can you pigeon hole the activities and achievements of the world’s equestrian travelers under the placid title of "trail riding."

Unfortunately one of the corrosive effects of trail riding is the demise of any sudden surprise and the eradication of true adventure. Trail riders are always sure of reaching their destination and finding therein a warm meal, a soft bed, and a safe roof. Ask any of the world’s equestrian explorers and they will laughingly tell you that no such safety net exists out on the high road to adventure.

Long Riders know instead the reality of aching bones encountered after a week of riding 50-mile days, or the bitter taste of disappointment that fills your mouth when you come to a village only to discover nothing for you or your horse to eat. They know the way the rain always finds a way to run down your neck no matter how many times you pull up your poncho with your cold, stiff fingers, or the fear that grips your stomach when your horse snorts and shies away from an unexpected stranger on a dark and lonely road.

Equestrian exploration is dangerous, life threatening, and exhilarating but it is never the placebo known as trail riding.

And you will seldom hear it explained but Long Riders are not akin to those in the ring either.

Ring riders are obedient to their customs, be it dressage, jumping or western pleasure. They travel in endless repetition in an attempt to strengthen what are basically emotional security patterns established with their horse. Their riding is not being used to meet any real risk, but rather to outrun it.

In contrast, hidden in equestrian travel are the secrets you will never find in the ring or on the trail. It’s the magic of riding to the crest of the mighty Shandur Pass as the sun is setting over the Karakoram Mountains. Sitting up there on your horse on top of the world you suddenly see the sky splashed with purple, pink, and gold. Behind you lies a tortured insult called a trail, but down below in the valley you see a village glowing warm with the welcome of twinkling lanterns. So you pat your horse’s neck and wish him a long life, a fair exchange for bringing you safely through yet again. Then you urge him to make his weary way down the darkening row of stony tiger’s teeth to the end of another day, one of many you will never be able to adequately describe to those not of your own special breed.

|

Click on photo to enlarge |

Basha O'Reilly crosses the steppes on her epic journey from Russia to England |

Ironically we are currently suffering from a famine of equestrian freedom. The 21st century has placed horse owners in a paradox. They have access to pampered equine athletes, synthetic space-age tack, cell phones, Global Positioning Satellite technology, insurance on both horse and rider, and a host of time saving gadgets. Yet when their souls become restless 99% of horse owners group like lemmings, never understanding that the traditional equestrian outlets favored today are not going to answer the spiritual void eating away at their experience starved souls.

What none of the equestrian magazines and horse whisperers are ever going to tell you is that travel on horseback brings with it a special kind of wisdom, helps you see through the world’s pretensions, and opens you up to the adventure of self-conquest. Equestrian travel is not merely about covering vast amounts of mileage. It is the journey you and your horse take together to reach the borders of an otherwise invisible place. It is a journey you see from the top of that altar of freedom, your saddle. It is an antidote to the world’s obsession with speed because the three-mile-per-hour pace of your horse forces you to slow down your body, which in turn results in the opening of your spirit. Thus an equestrian journey does not merely transport you along the physical road stretching ahead, more importantly it allows you to ride on the secret trail traced deep inside your soul.

The rare riders who undertake such a journey become saddle bound pilgrims leading a life based on physical freedom. Their horse takes them on a daily journey deeper away from the never-ending search for consumer products and shows them the way back to the nomadic principles of the past; grass, water, fire, and contemplation. These are the keys to equestrian travel. Such a journey transforms current equestrian stereotypes into spiritual equestrianism and develops the boutique rider into an equestrian mystic.

Earlier this year I hosted the world’s first international meeting of Long Riders.

Here were far-ranging roamers, men and women who had previously despaired of the everydayness of their lives. Our group was a confluence of countries and equestrian styles. Yet common to us all was the sense of awakened wonder we had each discovered with our horse.

Geldings, mares, or stallions, it made no difference. We had ridden them over the desolate portions of the world’s rough roads, while suffering disease, fighting off bandits, surviving deserts, swimming rivers, climbing mountains, and outwitting corrupt politicians. We were Long Riders who had surrendered homes and taken up saddles instead.

To us travel was a subject of study and an expansion of the mind. We had come together to confirm to ourselves, and each other, that we were equestrian nomads at heart, more willing to eat a crust of bread on the trail than be confined within four walls, albeit with the luxuries of rich meat and fine wine.

It was during this meeting that we agreed that at some time in each of our journeys our horses were revealed in a different light. Though our individual mounts had stood close by for years, after traveling they were no longer merely objects to be possessed. Thousands of hard miles and countless shared dangers had bonded us closer to our horses than to our mothers. The latter we loved. The former we entrusted with our lives on a daily basis. Travel had made human and horses part of a new herd dynamic. To us horses were no longer mute beasts. They were agents of change.

Here, we agreed, was the forgotten energy of the horse revealed.

The Long Rider’s Guild is part of a tradition stretching back to the Bronze Age. Not for us the attitude of Roman emperors. Those masquerading pedestrians had first introduced the concept of prestige transport, disguising the horse as an ostentatious demonstration of dispensable wealth. For us the horse was a freedom giver. He had shown us star patterns and mountain shapes, guided us through lands with no laws and few trails, and taught us that if we discovered fear on the road we could counter it with courage. The horse, we agreed, had showed us that the reason we journeyed was not to seek acclaim, but to discover happiness and the sacred source of life.

For three days and nights we spoke of nothing but horses and travel.

It was agreed that the purpose of The Long Rider’s Guild was to shed light in a time of darkness, to recapture the echoes of ancient nomadic equestrian cultures, and to seek out those equestrian elders who had already sought for the answers that tuned our own souls. If we were renegade pilgrims, at least we knew that we shared a common thread that included such illustrious equestrian explorers as George Beck, Aimé Tschiffely, Ana Beker, Roger Pocock, and Messanie Wilkins. We adjourned our meeting with the promise to share whatever wisdom we had been blessed with to those about to set out on their own journeys.

At this point let me hasten to add that I am not boasting that I’ve solved the puzzle of equestrian travel, only that I’ve spent twenty-plus-years carefully studying the pieces and players. I’ve been on the equestrian pilgrim’s road for a long, long time seeking answers to the technical and spiritual questions that I could never find at home. That is why, even after my horse died, I renewed my vow to seek out others of my kind. During the course of my horse trips I have learned that the meaning to my travels was hidden in the journey itself. In one obscure country or another it dawned on me that it was no longer important where I went, but rather what I sought. Somewhere along the trail I had become content to ride along with my horse and the wide world as silent companions.

Now I ask you, patient reader, if you own a horse why haven’t you surrendered to the pull of the horizon? What keeps you from giving in to the same sundown madness that pulled your forefathers and mothers towards the beckoning sea? Why, as you read this, do you not listen to the stirring of your own blood?

Find your courage!

Change the rhythm of your life!

People will say you are an impetuous fool for setting out, but their souls are dulled by the commonplace. Do not allow them to judge your actions by their base principles. They speak only to hide their own fear and cowardice.

I challenge you by saying that if you own a horse and have never ridden away from "home," then you are not truly bonded with the animal. You are a slave to the barn where you, the rider, hide your bravery. Real courage is leaving the ant-heap to ride where you wish, when you wish, as rapidly as you wish.

Think how free you will be if you saddle up and ride away. You will not only discover a poetry of riding, you will learn that the ride and the horse place a lasting spiritual fingerprint on your soul.

I leave you with this thought.

Truth seldom whispers to you and when it does the song is no louder than the beating of your heart.

No one can travel this road for you. Only you can summon the courage to ride the sacred trail of which I speak.

So go on.

What’s stopping you?

Saddle Up!

Main Stories from the Road page