Impressions of Andalusia

by

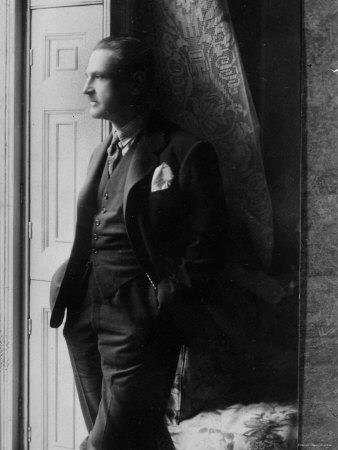

W. Somerset Maugham

Photo credit unknown

|

Impressions of Andalusia by W. Somerset Maugham |

|

William Somerset Maugham (1874 – 1965) was an English playwright, novelist and short story writer. He was among the most popular writers of his era and, reputedly, the highest paid author during the 1930s. His most famous books include "Of Human Bondage" and "The Razor's Edge." Yet prior to becoming a famous author, the twenty-three year old Englishman decided to seek adventure overseas. One of his earliest works dealt with the equestrian journey he made thorough Spain in 1898. In "The Land of the Blessed Virgin - Impressions of Andalusia" Maugham recounted his ride from Sevilla to Carmona and back. This accurate account captured the look and feel of a country before the onset of a deadly civil war and industrialization changed it forever.

I had a desire to see something of the very heart of Andalusia, of that part of the country which had preserved its antique character, where railway trains were not, and the horse, the mule, the donkey were still the only means of transit. After much scrutiny of local maps and conversation with horse-dealers and others, I determined from Seville to go circuitously to Ecija, and thence return by another route as best I could. The district I meant to traverse in olden times was notorious for its brigands; even thirty years ago the prosperous tradesman, voyaging on his mule from town to town, was liable to be seized by unromantic outlaws and detained till his friends forwarded ransom, while ears and fingers were playfully sent to prove identity.

In Southern Spain brigandage necessarily flourished, for not only were the country-folk in collusion with the bandits, but the very magistrates united with them to share the profits of lawless undertakings. Drastic measures were needful to put down the evil, and in a truly Spanish way drastic measures were employed. The Civil Guard, whose duty it was to see to the safety of the countryside, had no confidence in the justice of Madrid, whither captured highwaymen were sent for trial; once there, for a few hundred dollars, the most murderous ruffian could prove his babe-like innocence, forthwith return to the scene of his former exploits and begin again. So they hit upon an expedient. The Civil Guards set out for the capital with their prisoner handcuffed between them; but, curiously enough, in every single case the brigand had scarcely marched a couple of miles before he incautiously tried to escape, whereupon he was, of course, promptly shot through the back. People noticed two things: first, that the clothes of the dead man were often singed, as if he had not escaped very far before he was shot down; that only proved his guardians' zeal. But the other was stranger: the two Civil Guards, when after a couple of hours they returned to the town, as though by a mysterious premonition they had known the bandit would make some rash attempt, invariably had waiting for them an excellent hot dinner.

The only robber of importance who avoided such violent death was the chief of a celebrated band who, when captured, signed a declaration that he had not the remotest idea of escaping, and insisted on taking with him to Madrid his solicitor and a witness. He reached the capital alive, and having settled his little affairs with benevolent judges, turned to a different means of livelihood, and eventually, it is said, occupied a responsible post in the Government. It is satisfactory to think that his felonious talents were not in after-life entirely wasted.

It was the beginning of March when I started. According to the old proverb, the dog was already seeking the shade: En Marzo busca la sombra el perro; the chilly Spaniard, loosening the folds of his capa, acknowledged that at mid-day in the sun it was almost warm. The winter rains appeared to have ceased; the sky over Seville was cloudless, not with the intense azure of midsummer, but with a blue that seemed mixed with silver. And in the sun the brown water of the Guadalquivir glittered like the scales on a fish's back, or like the burnished gold of old Moorish pottery.

I set out in the morning early, with saddle-bags fixed on either side and poncho strapped to my pommel. A loaded revolver, though of course I never had a chance to use it, made me feel pleasantly adventurous. I walked cautiously over the slippery cobbles of the streets, disturbing the silence with the clatter of my horse's shoes. Now and then a mule or a donkey trotted by, with panniers full of vegetables, of charcoal or of bread, between which on the beast's neck sat perched a man in a short blouse. I came to the old rampart of the town, now a promenade; and at the gate groups of idlers, with cigarettes between their lips, stood talking.

An hospitable friend had offered lodging for the night and food; after which, my ideas of the probable accommodation being vague, I expected to sleep upon straw, for victuals depending on the wayside inns. I arrived at the “Campo de la Cruz”, a tiny chapel which marks the same distance from the Cathedral as Jesus Christ walked to the Cross; it is the final boundary of Seville.

Immediately afterwards I left the high-road, striking across country to Carmona. The land was already wild; on either side of the bridle-path were great wastes of sand covered only by palmetto. The air was cool and fresh, like the air of English country in June when it has rained through the night; and Aguador, snorting with pleasure, cantered over the uneven ground, nimbly avoiding holes and deep ruts with the sure-footedness of his Arab blood. An Andalusian horse cares nothing for the ground on which he goes, though it be hard and unyielding as iron; and he clambers up and down steep, rocky precipices as happily as he trots along a cinder-path.

I passed a shepherd in a ragged cloak and a broad-brimmed hat, holding a crook. He stared at me, his flock of brown sheep clustered about him as I scampered by, and his dog rushed after, barking.

Vaya Usted con Dios!

I came to little woods of pine-trees, with long, thin trunks, and the foliage spreading umbrella-wise; round them circled innumerable hawks, whose nests I saw among the branches. Two ravens crossed my path, their wings heavily flapping.

The great charm of the Andalusian country is that you seize romance, as it were, in the act. In northern lands it is only by a mental effort that you can realise the picturesque value of the life that surrounds you; and, for my part, I can perceive it only by putting it mentally in black and white, and reading it as though between the covers of a book. Once, I remember, in Brittany, in a distant corner of that rock-bound coast, I sat at midnight in a fisherman's cottage playing cards by the light of two tallow candles. Next door, with only a wall between us, a very old sailor lay dying in the great cupboard-bed which had belonged to his fathers before him; and he fought for life with the remains of that strenuous vigour with which in other years he had battled against the storms of the Atlantic. In the stillness of the night, the waves, with the murmur of a lullaby, washed gently upon the shingle, and the stars shone down from a clear sky. I looked at the yellow light on the faces of the players, gathered in that desolate spot from the four corners of the earth, and cried out: 'By Jove, this is romance!' I had never before caught that impression in the very making, and I was delighted with my good fortune.

The answer came quickly from the American: 'Don't talk bosh! It's your deal.'

But for all that it was romance, seized fugitively, and life at that moment threw itself into a decorative pattern fit to be remembered. It is the same effect which you get more constantly in Spain, so that the commonest things are transfigured into beauty. For in the cactus and the aloe and the broad fields of grain, in the mules with their wide panniers and the peasants, in the shepherds' huts and the straggling farm-houses, the romantic is there, needing no subtlety to be discovered; and the least imaginative may feel a certain thrill when he understands that the life he leads is not without its aesthetic meaning.

I rode for a long way in complete solitude, through many miles of this sandy desert. Then the country changed, and olive-groves in endless succession followed one another, the trees with curiously decorative effect were planted in long, even lines. The earth was a vivid red, contrasting with the blue sky and the sombre olives, gnarled and fantastically twisted, like evil spirits metamorphosed: in places they had sown corn, and the young green enhanced the shrill diversity of colour. With its clear, brilliant outlines and its lack of shadow, the scene reminded one of a prim pattern, such as in Jane Austen's day young gentlewomen worked in worsted. Sometimes I saw women among the trees, perched like monkeys on the branches, or standing below with large baskets; they were extraordinarily quaint in the trousers which modesty bade them wear for the concealment of their limbs when olive-picking. The costume was so masculine, their faces so red and weather-beaten, that the yellow handkerchief on their heads was really the only means of distinguishing their sex.

But the path became more precipitous, hewn from the sandstone, and so polished by the numberless shoes of donkeys and of mules that I hardly dared walk upon it; and suddenly I saw Carmona in front of me -- quite close.

The approach to Carmona is a very broad, white street, much too wide for the cottages which line it, deserted; and the young trees planted on either side are too small to give shade. The sun beat down with a fierce glare and the dust rose in clouds as I passed. Presently I came to a great Moorish gateway, a dark mass of stone, battlemented, with a lofty horseshoe arch. People were gathered about it in many-coloured groups, I found it was a holiday in Carmona, and the animation was unwonted; in a corner stood the hut of the Consumo, and the men advanced to examine my saddle-bags. I passed through, into the town, looking right and left for a parador, an hostelry whereat to leave my horse. I bargained for the price of food and saw Aguador comfortably stalled; then made my way to the Nekropolis where lived my host. There are many churches in Carmona, and into one of these I entered; it had nothing of great interest, but to a certain degree it was rich, rich in its gilded woodwork and in the brocade that adorned the pillars; and I felt that these Spanish churches lent a certain dignity to life: for all the careless flippancy of Andalusia they still remained to strike a nobler note. I forgot willingly that the land was priest-ridden and superstitious, so that a Spaniard could tell me bitterly that there were but two professions open to his countrymen, the priesthood and the bull-ring. It was pleasant to rest in that cool and fragrant darkness.

My host was an archaeologist, and we ate surrounded by broken earthenware, fragmentary mosaics, and grinning skulls. It was curious afterwards to wander in the graveyard which, with indefatigable zeal, he had excavated, among the tombs of forgotten races, letting oneself down to explore the subterranean cells. The paths he had made in the giant cemetery were lined with a vast number of square sandstone boxes which had contained human ashes; and now, when the lid was lifted, a green lizard or a scorpion darted out. From the hill I saw stretched before me the great valley of the Guadalquivir: with the squares of olive and of ploughed field, and the various greens of the corn, it was like a vast, multi-coloured carpet. But later, with the sunset, black clouds arose, splendidly piled upon one another; and the twilight air was chill and grey. A certain sternness came over the olive-groves, and they might well have served as a reproach to the facile Andaluz; for their cold passionless green seemed to offer a warning to his folly.

At night my host left me to sleep in the village, and I lay in bed alone in the little house among the tombs; it was very silent. The wind sprang up and blew about me, whistling through the windows, whistling weirdly; and I felt as though the multitudes that had been buried in that old cemetery filled the air with their serried numbers, a vast, silent congregation waiting motionless for they knew not what. I recalled a gruesome fact that my friend had told me: not far from there, in tombs that he had disinterred the skeletons lay huddled spasmodically, with broken skulls and a great stone by the side; for when a man, he said, lay sick unto death, his people took him, and placed him in his grave, and with the stone killed him.

In the morning I set out again. It was five-and-thirty miles to Ecija, but a new high road stretched from place to place and I expected easy riding. Carmona stands on the top of a precipitous hill, round which winds the beginning of the road; below, after many zigzags, I saw its continuation, a straight white line reaching as far as I could see. In Andalusia, till a few years ago, there were practically no high roads, and even now they are few and bad. The chief communication from town to town is usually an uneven track, which none attempts to keep up, with deep ruts, and palmetto growing on either side, and occasional pools of water. A day's rain makes it a quagmire, impassable for anything beside the sure-footed mule.

I went on, meeting now and then a string of asses, their panniers filled with stones or with wood for Carmona; the drivers sat on the rump of the hindmost animal, for that is the only comfortable way to ride a donkey. A peasant trotted briskly by on his mule, his wife behind him with her arms about his waist. I saw a row of ploughs in a field; to each were attached two oxen, and they went along heavily, one behind the other in regular line. By the side of every pair a man walked bearing a long goad, and one of them sang a Malaguena, its monotonous notes rising and falling slowly. From time to time I passed a white farm, a little way from the road, invitingly cool in the heat; the sun began to beat down fiercely. The inevitable storks were perched on a chimney, by their big nest; and when they flew in front of me, with their broad white wings and their red legs against the blue sky, they gave a quaint impression of a Japanese screen.

A farmhouse such as this seems to me always a type of the Spanish impenetrability. I have been over many of them, and know the manner of their rooms and the furniture, the round of duties there performed and how the day is portioned out; but the real life of the inhabitants escapes me. My knowledge is merely external. I am conscious that it is the same of the Andalusians generally, and am dismayed because I know practically nothing more after a good many years than I learnt in the first months of my acquaintance with them. Below the superficial similarity with the rest of Europe which of late they have acquired, there is a difference which makes it impossible to get at the bottom of their hearts. They have no openness as have the French and the Italians, with whom a good deal of intimacy is possible even to an Englishman, but on the contrary an Eastern reserve which continually baffles me. I cannot realise their thoughts nor their outlook. I feel always below the grace of their behaviour the instinctive, primeval hatred of the stranger.

Gradually the cultivation ceased, and I saw no further sign of human beings. I returned to the desert of the previous day, but the land was more dreary. The little groves of pine-trees had disappeared, there were no olives, no cornfields, not even the aloe nor the wilder cactus; but on either side as far as the horizon, desert wastes, littered with stones and with rough boulders, grown over only by palmetto. For many miles I went, dismounting now and then to stretch my legs and sauntering a while with the reins over my shoulder. Towards mid-day I rested by the wayside and let Aguador eat what grass he could.

Presently, continuing my journey, I caught sight of a little hovel where the fir-branch over the door told me wine was to be obtained. I fastened my horse to a ring in the wall, and, going in, found an aged crone who gave me a glass of that thin white wine, produce of the last year's vintage, which is called Vino de la Hoja, wine of the leaf; she looked at me incuriously as though she saw so many people and they were so much alike that none repaid particular scrutiny. I tried to talk with her, for it seemed a curious life that she must lead, alone in that hut many miles from the nearest hamlet, with never a house in sight; but she was taciturn and eyed me now with something like suspicion. I asked for food, but with a sullen frown she answered that she had none to spare. I inquired the distance to Luisiana, a village on the way to Ecija where I had proposed to lunch, and shrugging her shoulders, she replied: 'How should I know!' I was about to go when I heard a great clattering, and a horseman galloped up. He dismounted and walked in, a fine example of the Andalusian countryman, handsome and tall, well-shaved, with close-cropped hair. He wore elaborately decorated gaiters, the usual short, close-fitting jacket, and a broad-brimmed hat; in his belt were a knife and a revolver, and slung across his back a long gun. He would have made an admirable brigand of comic-opera; but was in point of fact a farmer riding, as he told me, to see his novia, or lady-love, at a neighbouring farm.

I found him more communicative and in the politest fashion we discussed the weather and the crops. He had been to Seville.

“Che maravilla!” he cried, waving his fine, strong hands. 'What a marvel! But I cannot bear the town-folk. What thieves and liars!'

'Town-folk should stick to the towns,' muttered the old woman, looking at me somewhat pointedly.

The remark drew the farmer's attention more closely to me.

'And what are you doing here?' he asked.

'Riding to Ecija.'

'Ah, you're a commercial traveller,' he cried, with fine scorn. 'You foreigners bleed the country of all its money. You and the government!'

'Rogues and vagabonds!' muttered the old woman.

Notwithstanding, the farmer with much condescension accepted one of my cigars, and made me drink with him a glass of aguardiente.

We went off together. The mare he rode was really magnificent, rather large, holding her head beautifully, with a tail that almost swept the ground. She carried as if it were nothing the heavy Spanish saddle, covered with a white sheep-skin, its high triangular pommel of polished wood. Our ways, however, quickly diverged. I inquired again how far it was to the nearest village.

'Eh!' said the farmer, with a vague gesture. 'Two leagues. Three leagues. Quien sabe? Who knows? Adios!' (Note: Originally a league referred to the distance a person or a horse could walk in an hour, which is why it can - infuriatingly - mean anything between three and four miles!)

He put the spurs to his mare and galloped down a bridle-track. I, whom no fair maiden awaited, trotted on soberly.

The endless desert grew rocky and less sandy, the colours duller. Even the palmetto found scanty sustenance, and huge boulders, strewn as though some vast torrent had passed through the plain, alone broke the desolate flatness. The dusty road pursued its way, invariably straight, neither turning to one side nor to the other, but continually in front of me, a long white line.

Finally in the distance I saw a group of white buildings and a cluster of trees. I thought it was Luisiana, but Luisiana, they had said, was a populous hamlet, and here were only two or three houses and not a soul. I rode up and found among the trees a tall white church, and a pool of murky water, further back a low, new edifice, which was evidently a monastery, and a posada. Presently a Franciscan monk in his brown cowl came out of the church, and he told me that Luisiana was a full league off, but that food could be obtained at the neighbouring inn.

The posada was merely a long barn, with an open roof of wood, on one side of which were half a dozen mangers and in a corner two mules. Against another wall were rough benches for travellers to sleep on. I dismounted and walked to the huge fireplace at one end, where I saw three very old women seated like witches round a brasero, the great brass dish of burning cinders. With true Spanish stolidity they did not rise as I approached, but waited for me to speak, looking at me indifferently. I asked whether I could have anything to eat.

'Fried eggs.'

'Anything else?'

The hostess, a tall creature, haggard and grim, shrugged her shoulders. Her jaws were toothless, and when she spoke it was difficult to understand. I tied Aguador to a manger and took off his saddle. The old women stirred themselves at last, and one brought a portion of chopped straw and a little barley. Another with the bellows blew on the cinders, and the third, taking eggs from a basket, fried them on the brasero. Besides, they gave me coarse brown bread and red wine, which was coarser still; for dessert the hostess went to the door and from a neighbouring tree plucked oranges.

When I had finished -- it was not a very substantial meal -- I drew my chair to the brasero and handed round my cigarette-case. The old women helped themselves, and a smile of thanks made the face of my gaunt hostess somewhat less repellent. We smoked a while in silence.

'Are you all alone here?' I asked, at length.

The hostess made a movement of her head towards the country. 'My son is out shooting,' she said, 'and two others are in Cuba, fighting the rebels.'

'God protect them!' muttered another.

'All our sons go to Cuba now,' said the first. 'Oh, I don't blame the Cubans, but the government.'

An angry light filled her eyes, and she lifted her clenched hand, cursing the rulers at Madrid who took her children. 'They're robbers and fools. Why can't they let Cuba go? It isn't worth the money we pay in taxes.'

She spoke so vehemently, mumbling the words between her toothless gums, that I could scarcely make them out.

'In Madrid they don't care if the country goes to rack and ruin so long as they fill their purses. Listen.' She put one hand on my arm. 'My boy came back with fever and dysentery. He was ill for months--at death's door--and I nursed him day and night. And almost before he could walk they sent him out again to that accursed country.'

The tears rolled heavily down her wrinkled cheeks.

Luisiana is a curious place. It was a colony formed by Charles III. of Spain with Germans whom he brought to people the desolate land; and I fancied the Teuton ancestry was apparent in the smaller civility of the inhabitants. They looked sullenly as I passed, and none gave the friendly Andalusian greeting. I saw a woman hanging clothes on the line outside her house; she had blue eyes and flaxen hair, a healthy red face, and a solidity of build which proved the purity of her northern blood. The houses, too, had a certain exotic quaintness; notwithstanding the universal whitewash of the South, there was about them still a northern character. They were prim and regularly built, with little plots of garden; the fences and the shutters were bright green. I almost expected to see German words on the post-office and on the tobacco-shop, and the grandiloquent Spanish seemed out of place; I thought the Spanish clothes of the men sat upon them uneasily.

The day was drawing to a close and I pushed on to reach Ecija before night, but Aguador was tired and I was obliged mostly to walk. Now the highway turned and twisted among little hills and it was a strange relief to leave the dead level of the plains: on each side the land was barren and desolate, and in the distance were dark mountains. The sky had clouded over, and the evening was grey and very cold; the solitude was awful. At last I overtook a pedlar plodding along by his donkey, the panniers filled to overflowing with china and glass, which he was taking to sell in Ecija. He wished to talk, but he was going too slowly, and I left him. I had hills to climb now, and at the top of each expected to see the town, but every time was disappointed. The traces of man surrounded me at last; again I rode among olive-groves and cornfields; the highway now was bordered with straggling aloes and with hedges of cactus.

At last! I reached the brink of another hill, and then, absolutely at my feet, so that I could have thrown a stone on its roofs, lay Ecija with its numberless steeples.

The central square, where are the government offices, the taverns, and a little inn, is a charming place, quiet and lackadaisical, its pale browns and greys very restful in the twilight, and harmonious. The houses with their queer windows and their balconies of wrought iron are built upon arcades which give a pleasant feeling of intimacy: in summer, cool and dark, they must be the promenade of all the gossips and the loungers. One can imagine the uneventful life, the monotonous round of existence; and yet the Andalusian blood runs in the people's veins. To my writer's fantasy Ecija seemed a fit background for some tragic story of passion or of crime.

I dined, unromantically enough, with a pair of commercial travellers, a post-office clerk, and two stout, elderly men who appeared to be retired officers. Spanish victuals are terrible and strange; food is even more an affair of birth than religion, since a man may change his faith, but hardly his manner of eating: the stomach used to roast meat and Yorkshire pudding rebels against Eastern cookery, and a Christian may sooner become a Buddhist than a beef-eater a guzzler of olla podrida. The Spaniards without weariness eat the same dinner day after day, year in, year out: it is always the same white, thin, oily soup; a dish of haricot beans and maize swimming in a revolting sauce; a nameless entrée fried in oil -- Andalusians have a passion for other animals' insides; a thin steak, tough as leather and grilled to utter dryness; raisins and oranges. You rise from table feeling that you have been soaked in rancid oil.

My table-companions were disposed to be sociable. The travellers desired to know whether I was there to sell anything, and one drew from his pocket, for my inspection, a case of watch-chains. The officers surmised that I had come from Gibraltar to spy the land, and to terrify me, spoke of the invincible strength of the Spanish forces.

'Are you aware,' said the elder, whose adiposity prevented his outward appearance from corresponding with his warlike heart, 'Are you aware that in the course of history our army has never once been defeated, and our fleet but twice?'

He mentioned the catastrophes, but I had never heard of them; and Trafalgar was certainly not included. I hazarded a discreet inquiry, whereupon, with much emphasis, both explained how on that occasion the Spanish had soundly thrashed old Nelson, although he had discomfited the French.

'It is odd,' I observed, 'that British historians should be so inaccurate.'

'It is discreditable,' retorted my acquaintance, with a certain severity.

'How long did the English take to conquer the Sudan?' remarked the other, somewhat aggressively picking his teeth. 'Twenty years? We conquered Morocco in three months.'

'And the Moors are devils,' said the commercial traveller. 'I know, because I once went to Tangiers for my firm.'

After dinner I wandered about the streets, past the great old houses of the nobles in the Calle de los Caballeros, empty now and dilapidated, for every gentleman that can put a penny in his pocket goes to Madrid to spend it; down to the river which flowed swiftly between high banks. Below the bridge two Moorish mills, irregular masses of blackness, stood finely against the night. Near at hand they were still working at a forge, and I watched the flying sparks as the smith hammered a horseshoe; the workers were like silhouettes in front of the leaping flames.

At many windows, to my envy, couples were philandering; the night was cold and Corydon stood huddled in his cape. But the murmuring as I passed was like the flow of a rapid brook, and I imagined, I am sure, far more passionate and romantic speeches than ever the lovers made. I might have uttered them to the moon, but I should have felt ridiculous, and it was more practical to jot them down afterwards in a note-book. In some of the surrounding villages they have so far preserved the Moorish style as to have no windows within reach of the ground, and lovers then must take advantage of the aperture at the bottom of the door made for the domestic cat's particular convenience. Stretched full length on the ground, on opposite sides of the impenetrable barrier, they can still whisper amorous commonplaces to one another. But imagine the confusion of a polite Spaniard, on a dark night, stumbling over a recumbent swain:

'My dear sir, I beg your pardon. I had no idea....'

In old days the disturbance would have been sufficient cause for a duel, but now manners are more peaceful: the gallant, turning a little, removes his hat and politely answers:

'It is of no consequence. Vaya Usted con Dios!'

'Good-night!'

The intruder passes and the beau endeavours passionately to catch sight of his mistress' black eyes.

Next day was Sunday, and I walked by the river till I found a plot of grass sheltered from the wind by a bristly hedge of cactus. I lay down in the sun, lazily watching two oxen that ploughed a neighbouring field.

I felt it my duty in the morning to buy a chap-book relating the adventures of the famous brigands who were called the Seven Children of Ecija; and this, somewhat sleepily, I began to read. It required a Byronic stomach, for the very first chapter led me to a monastery where mass proceeded in memory of some victim of undiscovered crime. Seven handsome men appeared, most splendidly arrayed, but armed to the teeth; each one was every inch a brigand, pitiless yet great of heart, saturnine yet gentlemanly; and their peculiarity was that though six were killed one day seven would invariably be seen the next. The most gorgeously apparelled of them all, entering the sacristy, flung a purse of gold to the Superior, while a scalding tear coursed down his sunburnt cheek; and this he dried with a noble gesture and a richly embroidered handkerchief! In a whirlwind of romantic properties I read of a wicked miser who refused to support his brother's widow, of the widow herself, (brought at birth to a gardener in the dead of night by a mysterious mulatto,) and of this lady's lovely offspring. My own feelings can never be harrowed on behalf of a widow with a marriageable daughter, but I am aware that habitual readers of romance, like ostriches, will swallow anything. I was hurried to a subterranean chamber where the Seven Children, in still more elaborate garments, performed various dark deeds, smoked expensive Havanas, and seated on silken cushions, partook (like Freemasons) of a succulent cold collation.

The sun shone down with comfortable warmth, and I stretched my legs. My pipe was out and I refilled it. A meditative snail crawled up and observed me with flattering interest.

I grew somewhat confused. A stolen will was of course inevitable, and so were prison dungeons; but the characters had an irritating trick of revealing at critical moments that they were long-lost relatives. It must have been a tedious age when poor relations were never safely buried. However, youth and beauty were at last triumphant and villainy confounded, virtue was crowned with orange blossom and vice died a miserable death. Rejoicing in duty performed I went to sleep.

But next morning the sky was dark with clouds; people looked up dubiously when I asked the way and distance to Marchena, prophesying rain. Fetching my horse, the owner of the stable robbed me with peculiar callousness, for he had bound my hands the day before, when I went to see how Aguador was treated, by giving me with most courteous ceremony a glass of aguardiente; and his urbanity was then so captivating that now I lacked assurance to protest. I paid the scandalous overcharge with a good grace, finding some solace in the reflection that he was at least a picturesque blackguard, tall and spare, grey-headed, with fine features sharpened by age to the strongest lines; for I am always grateful to the dishonest when they add a certain aesthetic charm to their crooked ways. There is a proverb which says that in Ecija every man is a thief and every woman -- no better than she should be: I was not disinclined to believe it.

I set out, guided by a sign-post, and the good road seemed to promise an easy day. They had told me that the distance was only six leagues, and I expected to arrive before luncheon. Aguador, fresh after his day's rest, broke into a canter when I put him on the green plot, which the old Spanish law orders to be left for cattle by the side of the highway. But after three miles, without warning, the road suddenly stopped. I found myself in an olive-grove, with only a narrow path in front of me. It looked doubtful, but there was no one in sight and I wandered on, trusting to luck.

Presently, in a clearing, I caught sight of three men on donkeys, walking slowly one after the other, and I galloped after to ask my way. The beasts were laden with undressed skins which they were taking to Fuentes, and each man squatted cross-legged on the top of his load. The hindermost turned right round when I asked my question and sat unconcernedly with his back to the donkey's head. He looked about him vaguely as though expecting the information I sought to be written on the trunk of an olive-tree, and scratched his head.

'Well,' he said, 'I should think it was a matter of seven leagues, but it will rain before you get there.'

'This is the right way, isn't it?'

'It may be. If it doesn't lead to Marchena it must lead somewhere else.'

There was a philosophic ring about the answer which made up for the uncertainty. The skinner was a fat, good-humoured creature, like all Spaniards intensely curious; and to prepare the way for inquiries, offered a cigarette.

'But why do you come to Ecija by so roundabout a way as Carmona, and why should you return to Seville by such a route as Marchena?'

His opinion was evidently that the shortest way between two places was also the best. He received my explanation with incredulity and asked, more insistently, why I went to Ecija on horseback when I might go by train to Madrid.

'For pleasure,' said I.

'My good sir, you must have come on some errand.'

'Oh yes,' I answered, hoping to satisfy him, 'on the search for emotion.'

At this he bellowed with laughter and turned round to tell his fellows.

'Usted es muy guason,' he said at length, which may be translated: 'You're a mighty funny fellow.'

I expressed my pleasure at having provided the skinners with amusement and bidding them farewell, trotted on.

I went for a long time among the interminable olives, grey and sad beneath the sullen clouds, and at last the rain began to fall. I saw a farm not very far away and cantered up to ask for shelter. An old woman and a labourer came to the door and looked at me very doubtfully; they said it was not a posada, but my soft words turned their hearts and they allowed me to come in. The rain poured down in heavy, oblique lines.

The labourer took Aguador to the stable and I went into the parlour, a long, low, airy chamber like the refectory of a monastery, with windows reaching to the ground. Two girls were sitting round the brasero, sewing; they offered me a chair by their side, and as the rain fell steadily we began to talk. The old woman discreetly remained away. They asked about my journey, and as is the Spanish mode, about my country, myself, and my belongings. It was a regular volley of questions I had to answer, but they sounded pleasanter in the mouth of a pretty girl than in that of an obese old skinner; and the rippling laughter which greeted my replies made me feel quite witty. When they smiled they showed the whitest teeth. Then came my turn for questioning. The girl on my right, prettier than her sister, was very Spanish, with black, expressive eyes, an olive skin, and a bunch of violets in her abundant hair. I asked whether she had a novio, or lover; and the question set her laughing immoderately. What was her name? 'Soledad -- Solitude.'

I looked somewhat anxiously at the weather, I feared the shower would cease, and in a minute, alas! the rain passed away; and I was forced to notice it, for the sun-rays came dancing through the window, importunately, making patterns of light upon the floor. I had no further excuse to stay, and said good-bye; but I begged for the bunch of violets in Soledad's dark hair and she gave it with a pretty smile. I plunged again into the endless olive-groves.

It was a little strange, the momentary irruption into other people's lives, the friendly gossip with persons of a different tongue and country, whom I had never seen before, whom I should never see again; and were I not strictly truthful I might here lighten my narrative by the invention of a charming and romantic adventure. But if chance brings us often for a moment into other existences, it takes us out with equal suddenness so that we scarcely know whether they were real or mere imaginings of an idle hour: the Fates have a passion for the unfinished sketch and seldom trouble to unravel the threads which they have so laboriously entangled. The little scene brought another to my mind. When I was 'on accident duty' at St. Thomas's Hospital a man brought his son with a broken leg; it was hard luck on the little chap, for he was seated peacefully on the ground when another boy, climbing a wall, fell on him and did the damage. When I returned him, duly bandaged, to his father's arms, the child bent forward and put out his lips for a kiss, saying good-night with babyish pronunciation. The father and the attendant nurse laughed, and I, being young, was confused and blushed profusely. They went away and somehow or other I never saw them again. I wonder if the pretty child, (he must be eight or ten now,) remembers kissing a very weary medical student, who had not slept much for several days, and was dead tired. Probably he has quite forgotten that he ever broke his leg. And I suppose no recollection remains with the pretty girl in the farm of a foreigner riding mysteriously through the olive-groves, to whom she gave shelter and a bunch of violets.

I came at last to the end of the trees and found then that a mighty wind had risen, which blew straight in my teeth. It was hard work to ride against it, but I saw a white town in the distance, on a hill; and made for it, rejoicing in the prospect. Presently I met some men shooting, and to make sure, asked whether the houses I saw really were Marchena.

'Oh no,' said one. 'You've come quite out of the way. That is Fuentes. Marchena is over there, beyond the hill.'

My heart sank, for I was growing very hungry, and I asked whether I could not get shelter at Fuentes. They shrugged their shoulders and advised me to go to Marchena, which had a small inn. I went on for several hours, battling against the wind, bent down in order to expose myself as little as possible, over a huge expanse of pasture land, a desert of green. I reached the crest of the hill, but there was no sign of Marchena, unless that was a tower which I saw very far away, its summit just rising above the horizon.

I was ravenous. My saddle-bags contained spaces for a bottle and for food; and I cursed my folly in stuffing them with such useless refinements of civilisation as hair-brushes and soap. It is possible that one could allay the pangs of hunger with soap; but under no imaginable circumstances with hair-brushes.

It was a tower in the distance, but it seemed to grow neither nearer nor larger; the wind blew without pity, and miserably Aguador tramped on. I no longer felt very hungry, but dreadfully bored. In that waste of greenery the only living things beside myself were a troop of swallows that had accompanied me for miles. They flew close to the ground, in front of me, circling round; and the wind was so high that they could scarcely advance against it.

I remembered the skinner's question, why I rode through the country when I could go by train. I thought of the Cheshire Cheese in Fleet Street, where persons more fortunate than I had that day eaten hearty luncheons. I imagined to myself a well-grilled steak with boiled potatoes, and a pint of old ale, Stilton! The smoke rose to my nostrils.

But at last, the Saints be praised! I found a real bridle-path, signs of civilisation, ploughed fields; and I came in sight of Marchena perched on a hill-top, surrounded by its walls. When I arrived the sun was setting finely behind the town.

Marchena was all white, and on the cold windy evening I spent there, deserted of inhabitants. Quite rarely a man sidled past wrapped to the eyes in his cloak, or a woman with a black shawl over her head. I saw in the town nothing characteristic but the wicker-work frame in front of each window, so that people within could not possibly be seen; it was evidently a Moorish survival. At night men came into the eating-room of the inn, ate their dinner silently, and muffling themselves, quickly went out; the cold seemed to have killed all life in them. I slept in a little windowless cellar, on a straw bed which was somewhat verminous.

But next morning, as I looked back, the view of Marchena was charming. It stood on the crest of a green hill, surrounded by old battlements, and the sun shone down upon it. The wind had fallen, and in the early hour the air was pleasant and balmy. There was no road whatever, not even a bridle-track this time, and I made straight for Seville. I proposed to rest my horse and lunch at Mairena. On one side was a great plain of young corn stretching to the horizon, and on the other, with the same mantle of green, little hills, round which I slowly wound. The sun gave all manner of varied tints to the verdure -- sometimes it was all emerald and gold, and at others it was like dark green velvet.

But the clouds in the direction of Seville were very black, and coming nearer I saw that it rained upon the hills. The water fell on the earth like a transparent sheet of grey. Soon I felt an occasional drop, and I put on my poncho.

The rain began in earnest, no northern drizzle, but a streaming downpour that soaked me to the skin. The path became marsh-like, and Aguador splashed along at a walk; it was impossible to go faster. The rain pelted down, blinding me. Then, oddly enough, for the occasion hardly warranted such high-flown thoughts, I felt suddenly the utter helplessness of man: I had never before realised with such completeness his insignificance beside the might of Nature; alone, with not a soul in sight, I felt strangely powerless. The plain flaunted itself insolently in face of my distress, and the hills raised their heads with a scornful pride; they met the rain as equals, but me it crushed; I felt as though it would beat me down into the mire. I fell into a passion with the elements, and was seized with a desire to strike out. But the white sheet of water was senseless and impalpable, and I relieved myself by raging inwardly at the fools who complain of civilisation and of railway-trains; they have never walked for hours foot-deep in mud, terrified lest their horse should slip, with the rain falling as though it would never cease.

The path led me to a river; there was a ford, but the water was very high, and rushed and foamed like a torrent. Ignorant of the depth and mistrustful, I trotted up-stream a little, seeking shallower parts; but none could be seen, and it was no use to look for a bridge. I was bound to cross, and I had to risk it; my only consolation was that even if Aguador could not stand, I was already so wet that I could hardly get wetter. The good horse required some persuasion before he would enter; the water rushed and bubbled and rapidly became deeper; he stopped and tried to turn back, but I urged him on. My feet went under water, and soon it was up to my knees; then, absurdly, it struck me as rather funny, and I began to laugh; I could not help thinking how foolish I should look and feel on arriving at the other side, if I had to swim for it. But immediately it grew shallower; all my adventures tailed off thus unheroically just when they began to grow exciting, and in a minute I was on comparatively dry land.

I went on, still with no view of Mairena; but I was coming nearer. I met a group of women walking with their petticoats over their heads. I passed a labourer sheltered behind a hedge, while his oxen stood in a field, looking miserably at the rain. Still it fell, still it fell!

And when I reached Mairena it was the most cheerless place I had come across on my journey, merely a poverty-stricken hamlet that did not even boast a bad inn. I was directed from place to place before I could find a stable; I was soaked to the skin, and there seemed no shelter. At last I discovered a wretched wine-shop; but the woman who kept it said there was no fire and no food. Then I grew very cross. I explained with heat that I had money; it is true I was bedraggled and disreputable, but when I showed some coins, to prove that I could pay for what I bought, she asked unwillingly what I required. I ordered a brasero, and dried my clothes as best I could by the burning cinders. I ate a scanty meal of eggs, and comforted myself with the thin wine of the leaf, sufficiently alcoholic to be exhilarating, and finally, with aguardiente regained my equilibrium.

But the elements were against me. The rain had ceased while I lunched, but no sooner had I left Mairena than it began again, and Seville was sixteen miles away. It poured steadily. I tramped up the hills, covered with nut-trees; I wound down into valleys; the way seemed interminable. I tramped on. At last from the brow of a hill I saw in the distance the Giralda and the clustering houses of Seville, but all grey in the wet; above it heavy clouds were lowering. On and on!

The day was declining, and Seville now was almost hidden in the mist, but I reached a road. I came to the first tavern of the environs; after a while to the first houses, then the road gave way to slippery cobbles, and I was in Seville. The Saints be praised!