How to Ride East to West across Australia

by

Stef Gebbie

|

How to Ride East to West across Australia by Stef Gebbie

|

|

In 2019 Stef Gebbie rode 4,485 kilometres (2786 miles) across the Australian continent. The solo journey began at the mouth of the Snowy River on the east coast of Victoria and finished at the Margaret River on the west coast of Western Australia. Accompanied by her 17-year-old Arabian, Mr Richard, and her 3-year-old stock horse Micky, the trio travelled for more than seven months (235 days). Upon completing this special report, Stef said, I hope the information below helps to answer all the questions I had prior to setting out, and hopefully inspires others to undertake a bold and audacious long distance horse trek.

|

Finding Your Horses |

I was lucky heading into this trip, as I already had a trusty steed in Mr Richard, my 17-year-old Arab that I have had since he was a colt. We had done quite a few week to ten day treks at home in Tasmania, and I knew the depths of his bravery and endurance. However, there is a reason most old timers will raise their eyebrows if you say you are heading out on a long distance trek with only one horse: it's a whole lot harder than having two. Not to say it can't be done, but you simply don't have the flexibility and capacity for carrying more food (both human and horse) that you have with both a pack and a riding horse. So I picked up another horse, my sweet piebald stock horse Micky a week into the trek.

If you are planning a long distance journey and you live in Australia, you probably have horses already or know people who do who can help you find a suitable horse. However, if you are coming from overseas, you might find it a bit difficult to find a good horse. The main reason for this is that the majority of people in Australia ride for pleasure, and have horses that have never done anything more adventurous than get on a float (trailer) down to the local gymkhana. Taking a fussy spoiled horse out onto the road without knowing his temperament is a recipe for a failed trip. This is why buying a horse from the mountains, in the high country of Victoria and New South Wales, or a well trained stock horse is a good idea. These horses have usually been packed, hobbled and exposed to all kinds of things you will meet on the road (dogs, cattle, trucks, motorcycles, etc).

The idea of getting to know your horses before setting out sounds extremely sound. However, I personally found that it doesn't take long for the horses to settle into a life on the road and sometimes when you HAVE to do something, such a cross a river, it can be a lot calmer than trying to simulate a situation. Whatever happens on the road, you will deal with it calmly and in order, and that will force your horses to do likewise. Or at least that is my personal experience.

|

Planning Your Route |

Australia is no country for horses.

The vast majority of the interior is devoid of edible vegetation. The areas in the south and east and along the coast in the west that are arable are subject to extreme weather events such as droughts that can last years, floods in the rainy season and catastrophic bushfires in the dry season. This is something to bear in mind at all times: the landscape, no matter where you are, is almost always vaguely hostile to horses. Most native vegetation cannot be eaten. The grass that grows in the farmlands can dry out to nothing in the summer. The price of hay can be pushed up to more than $20 Australian dollars per bale by drought.

That being said, I crossed Australia during a drought, between two of the hottest summers on record, and finished the trip with horses in better condition than when I started. The key to this was choosing a sensible route.

I found the most valuable resource was satellite imagery. Topographic maps were great in the Victorian high country, but after that, the countryside is basically flat, and the information gained from satellite images was invaluable. It was easy to see where there was farmland and irrigated crops and where there were large towns to avoid. Rivers and watercourses and even dams in paddocks all show up clearly. The line between salt scrub and farmland was clear, as was the cleared areas through forests bereft of feed. I found the best way of route planning was to know where you were going vaguely, a series of stepping stones sketched out via satellite and then work out the best way to get there on the ground.

Some highways had lovely tracks running on the verge beside them, which show up on satellite. Some did not, and the best way was to follow as many minor farming back roads as possible. Somewhat counter-intuitively, some of the most dangerous roads were the relatively minor sealed roads; they would usually have little shoulder and yet have enough fast traffic as to be dangerous.

Crossing such an arid continent, water is a major consideration. Again, satellite imagery was the key. Wherever there are farms, there is water. Wherever there are houses, there is water. Crossing the major stretch of barren ground across the Nullarbor, I was lucky to have the vehicle support of a friend. The Nullarbor Plain is part of the area of flat, almost treeless, arid or semi-arid country of southern Australia, located on the Great Australian Bight coast with the Great Victoria Desert to its north.

The only time satellite let me down was a few weeks in Western Australia, after the Nullabor when it was just me and my horses again. According to the imagery, there were dams every few kilometres across the wheat belt. What did not show up was the fact that many of these dams were too saline to drink. We managed without too much trouble, finding stock water or asking at homesteads, but it was something I had not considered.

It was always interesting to talk with locals regarding feed and routes, but not always helpful (more on this below).

|

Weather |

Australia is the driest continent on earth and it is getting hotter every year. If you are planning on crossing it East to West, the biggest thing to considered is the weather; specifically, the summer.

Even in the east and along the coast, where most of Australia's farmland and most hospitable country for horses is, the summers are hot and dry. The feed dries out and temperatures regularly reach the mid-thirties Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit) and higher. The central arid regions become impassable to a sane person. And then there is the real threat of bushfires.

I left the Victorian coast in the middle of April. This meant I was through the high country before the snow, and out along the Murray River as the autumn grass was in full growth. Even though everyone told me how dry a year it had been, I didn't have to worry about feed for more than 1,000 kilometres (621 miles). This green growth kept us pretty well for long sections in eastern South Australia, and then once out on the Nullarbor and whenever we crossed mallee country before that, we had to carry all our feed, so the weather was significant not so much for grass but for temperature.

|

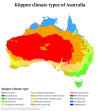

Australian Climate Map |

We headed out across the Nullarbor at the middle of August, and were on the other side by early October. This meant the daily temperatures were usually pleasant and we only had a few days that reached the low 30s. However, we then had a three week break whilst waiting for quarantine, which was impossible to avoid at the time, but retrospectively would have been best to organise a bit better to avoid.... or perhaps leave three weeks earlier! Because it meant we were crossing the Western Australian wheat belt in November and the beginning of December, when temperatures regularly got up to the mid to high 30s and topped 40 degrees degree Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) several times. This meant I had to get up at 2.30 a.m. most mornings to get the necessary miles done each day to get us to the west coast in time to catch the last truck of the year back home.

And the flies started to get really bad little black bush flies that fortunately do not sting, but are their own kind of mental torture that has to be endured to be believed.

We returned home in Tasmania by the middle of December, just as one of the worst bushfire season picked up on the mainland. Vast swathes of the country were on fire, including many areas we had recently ridden through, particularly the Victorian High Country and the dry eucalypt forests in Western Australia.

|

Australian Bush Fires in 2019 |

It was a sobering reminder that travelling on horseback in Australia in summer is best avoided. Bushfires are a serious threat and are something you should thoroughly consider when planning.

|

Gear & Tack |

I rode in a flexible Trekker saddle because my Arab has an impossibly strange shaped back. This saddle was great and was easily adjusted to fit both horses. If I had a normal horse however I would probably opt for a more traditional saddle, but have to say the Trekker performed admirably. Good stock saddles are readily available in Australia.

Pack saddles are harder to come by. I was lucky enough to find an adjustable Canadian pack saddle in the tiny town where I bought my second horse, but generally speaking, it's almost impossible to get a second hand pack saddle for love or money. Your best bet is to buy from the US, or if you are coming from overseas, bring your own. There is also not a vast array of packing gear (such as saddle bags etc) readily available, but everything can of course be purchased online.

Use a low-profile string girth and lots of padding under the saddles.

|

Horse Care |

There is absolutely no point undertaking a long distance horse trek if your horses are not happy and healthy!

They should be loving life and glowing with health.

Life on the road closely resembles the conditions under which horses evolved, so if you are doing your job right, they should be having the time of their lives. Yes, there will be lean times. Yes, there will be hot weather and cold, terrifying traffic and howling winds, but if your horses are losing condition or looking consistently dispirited, you are doing something wrong and need to find a solution.

Feeding horses on the road is the single most vital part of horse travel and was literally the only thing I really thought about for seven and a half months. Grass is well and good if you can find it. Otherwise Lucerne hay was the best thing I fed them. Various hard feeds are great but expensive, but at the end of the day, expense should not be an issue where your horses' health is concerned.

A mineral supplement is essential. I found the most useful product to be a pro-biotic powder called Inside-Out which kept my ponies glowing and I think helped ensure we never had any problems with colic etc. Finding enough roughage is a constant consideration. I found the horses to be surprisingly resilient, and they absolutely thrived on a diet of wheat when we were crossing through the wheat belt in Western Australia. Hoof care is vital. I went barefoot and used Renegade Viper hoof boots. I did all my own trimming and the horses' feet have never looked so good. They were hard and sound as a bell.

Monitor backs for discomfort and make changes accordingly.

Get off and walk a lot. This is good for your horse and good for your knees!

|

Learn from the Locals |

Everyone I met was a various combination of intrigued, baffled and generous. People were more than willing to help and I was often blown away by the generosity and hospitality shown to us, by folks we met along the way and the community that built up around my blog online.

That being said, almost no one undertakes long distance horse treks. Most locals I met along the way meant well, but their advice could be called haphazard at best. Not from ill-intent, but simply because nobody has ever considered what you need to consider when riding across a continent.

People's advice would often directly contradict. For example, there was a highway crossing the Flinders Ranges in South Australia. Everyone agreed it was windy and too dangerous to ride a horse along. However the advice I received on how to get around it varied from offers of driving me and the horses over the range to riding for 70 kilometres (44 miles) north to avoid the pass, to explicit warnings against trying to find a way cross country as they were real mountains.

It's always helpful to listen politely and ask questions, but you are not obliged to follow anyone's advice. In the end, I headed over the range cross country, and it was one of the best days of the whole trip. So gather as much information from locals as you can, but make your own decisions.

Another thing to bear in mind is that even people with horses often have little conception of long distance horse travel, and they are often the ones most likely to judge you harshly. However, if your horses are happy and healthy (as they will be if you are doing it right), then you should have nothing to fear from this kind of judgement.

|

Food |

There are plenty of opportunities to replenish human food in towns spaced every week or so until one reaches Penong, which is the last shop for 1,000 kilometres (621 miles) as one crosses the Nullarbor. It is often hard to know what a small town has to offer in regards to shops and supplies. Usually a quick Google will turn up the supermarkets, but it can be harder to track down fodder suppliers.

Most farmers are happy to spare some hay, and in areas that are relatively populated and folks keep horses, you will be able to purchase hay, but bear in mind that in drought the price of a square bale can easily top $20 and folks may not be willing to part with large amounts. When we approached the Nullarbor, I had a friend with a vehicle and float (trailer) supporting me. It was filled with hay purchased in the eastern states and hard feed for 2 months, plus 800 litres of water, as well as human food for that length of time.

Water out on the Nullarbor is scarce, and although there are road houses every 150 kilometres (94 miles) or so, they are often reluctant to hand over vast amounts of water for thirsty horses, who drink about 80 litres (22 gallons) a day. This is a major consideration.

|

Safety |

Every time you ride on a road, you are putting your life, your horses' lives, and the lives of other road users at risk!

Roads, especially highways, are not designed with horses and riders in mind.

Cars are dangerous and horses are unpredictable, and add in drivers that rarely see horses on the road and probably don't know how to react when they do and you have a nightmare combination.

Use vast amounts of both caution and common sense whenever riding on a road.

Stop and turn your horses to face large trucks or strange shaped machinery.

Be ready to plunge into thick vegetation or down into a ditch to avoid dangerous situations.

Try to avoid highways and major sealed roads. Riding on unsealed country roads is a pleasant experience, with traffic being both less in volume and more considerate in attitude, with the extra advantage that people are usually in less of a hurry and have time to stop and chat.

Meeting a truck on a back road is a totally different experience to meeting one doing 110 kilometres an hour on a highway. People are much more polite on country roads. I found there were often minor tracks and motorbike trails running along the verges of highways which make life so much easier and much safer.

Check the weather regularly. It's quite easy to change your plans according to a forecast and therefore avoid trouble from extreme heat, storms or even just and standard rainy day.

Bear in mind that riding on sealed roads and along highways is even more dangerous during rain.

Carry emergency communication technology. I found the Garmin Inreach Explorer to be invaluable. It works as a standard GPS, has a built in SOS function like a PLB, and allows you to send text messages and emails to anyone around the world using satellite. It also provides a basic weather forecasting service.